details from Urania, 2015, off-set litho posters

‘Many Maids Make Much Noise’, 2015

solo show, ar/ge kunst, Bolzano, curated by Emanuele Guidi

‘Many Maids Make Much Noise’ takes its title from a voice exercise that was given to me during voice therapy, when I underwent rehabilitation in order to learn to speak again, following a virus which had left my vocal chords damaged. The exhibition revolves around the subjects that preoccupied me during a whole year of silence, as I was forced to consider the dual nature of the voice as something at once symbolic and also an actual instrument that forms part of our bodies. The artworks touch on those places where the personal and the political intersect, and the effects that institutions and structures of power can have upon the most intimate parts of our lives, such as our sexuality and our health. I am interested in the act of speaking in public: who exactly feels they have the right to do it, who doesn’t and why? The exhibition comprises a sound installation titled Learning to Speak Sense (2015), works in fabric that include a hand-sewn quilt titled To Our Friends (2015), and a poster series Urania: Star Dust Index (2015).

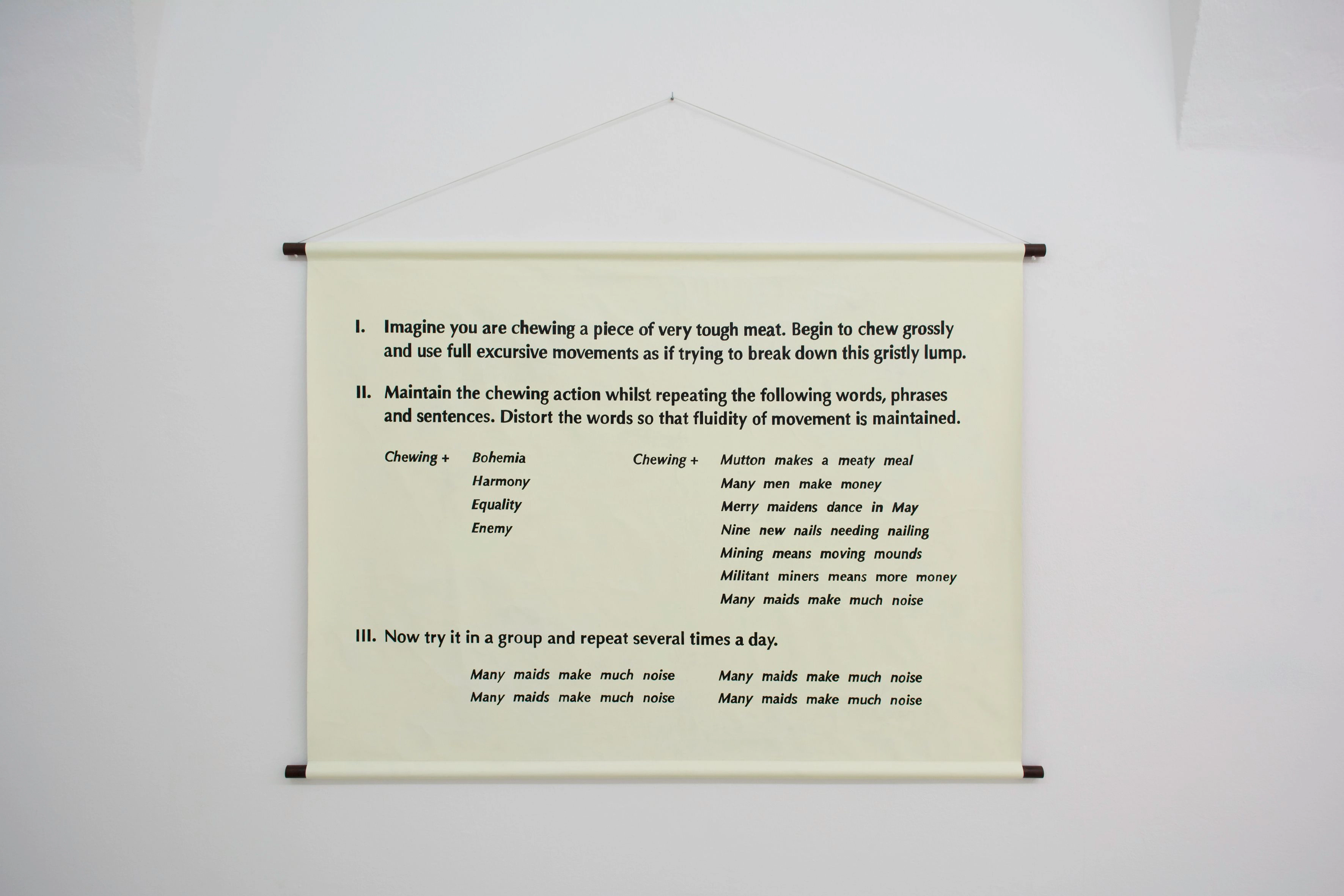

Learning to Speak Sense, 2015

acrylic paint on canvas, wood, string, 200 x 125 cm (detail of sound installation)

Learning to Speak Sense, 2015

sound installation, 12 min. 37 sec.

Learning to Speak Sense, 2015

sound installation

Learning to Speak Sense is a sound installation in which lines of instructions for voice exercises hang on the wall, like nineteenth-century school posters designed for elocution lessons. The viewer hears a pedagogical situation unfold, in which a male teacher is training me to speak ‘sense’, highlighting the disciplining aspect of voice therapy. The piece was made in collaboration with voice coach Geoffrey Brumlik. During my rehabilitation I repeated these exercises several times a day, as I learnt to articulate again. Hidden among absurd ‘nonsense’ sounds are sentences that seem to be ideological, such as the phrases ‘Militant Miners Means More Money’ and ‘Many Maids Make Much Noise’. I began to speculate about the anonymous author of these words: was it a care worker employed by the hospital where I received treatment, whose messages are clandestinely distributed through the bodies of individuals learning to find a voice? The exercises appear to address militancy and the act of speaking itself – what it means to collectively ‘make noise’ in order to be heard in public. In Learning to Speak Sense they are combined with words written by activist Sylvia Pankhurst: a visceral description of the effect that hunger strike has on the mouth and body, by a woman who was repeatedly imprisoned by the authorities for refusing to be silenced.

Learning to Speak Sense was made into a performance in 2019, for the ‘Idiorhythmias’ festival at Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona (MACBA).

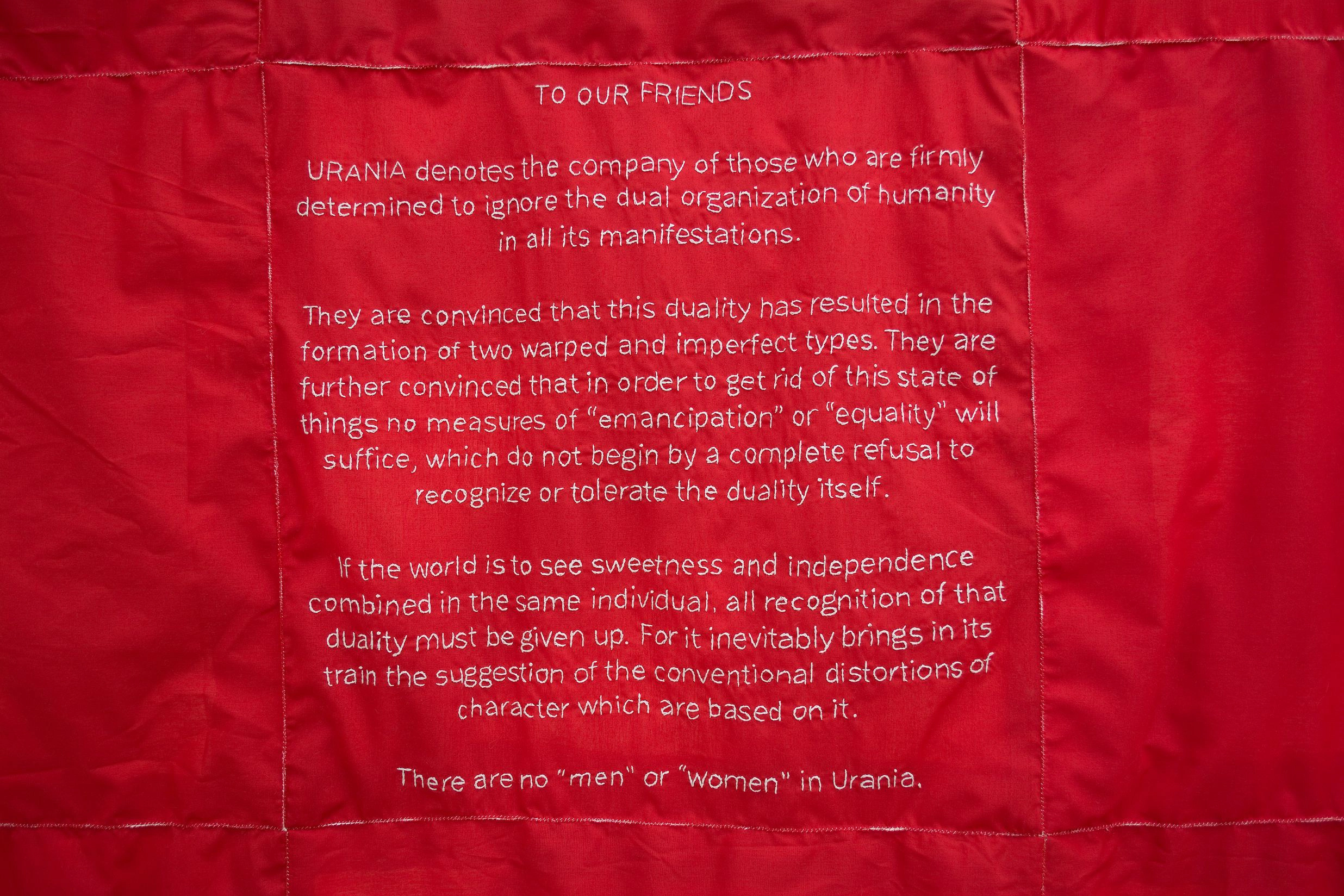

To Our Friends, 2015

hand-sewn fabric quilt, 231 x 235cm (detail)

To Our Friends, 2015

fabric quilt, 200 x 200 cm

During my recovery from long-term illness, I hand-sewed this quilt for my own bed in order to stave off the boredom and frustration of not being able to speak. On the back of this intimate object sits a secret panel, embroidered with the mission statement of Urania magazine, which was published at the beginning of every issue.

To Our Friends, 2015

hand-sewn fabric quilt, 231 x 235cm (detail)

Interview with Olivia Plender by Elena Bordignon for the online journal ATP Diary, about her solo exhibition at ar/ge kunst, Bolzano, titled ‘Many Maids Make Much Noise’

ATP: Your exhibition is closing a series of events on the occasion of the thirtieth anniversary of ar/ge kunst. The various artists who contributed this year have been invited to reflect on the concept of ‘ar/ge kunst’ as Arbeitsgemeinschaft or ‘work group’. What are the considerations you engaged with in the project that you recently opened in Bolzano?

Olivia Plender: I am drawn to the idea of the ‘work group’ because I often work collaboratively. This brings up interesting practical problems, such as group dynamics, the distribution of power, collective decision-making and so on, as well as ethical questions about representation and authorship. However, in this exhibition the idea of the ‘work group’ is present on more of a thematic level. Much of my work as an artist results from historical research into social movements from the past, and most recently I have been looking at the British suffragette movement – the militant wing of the early twentieth-century campaign for the right to vote for women. Lately I’ve been thinking about how the big collective public actions, such as the protests and manifestations of militancy that that movement is famous for, were underpinned by private networks of friendship and care. Ways of working, living and being together that are less visible to history, but no less important in terms of the struggle to change opinions and practices, claim space and have one’s voice heard.

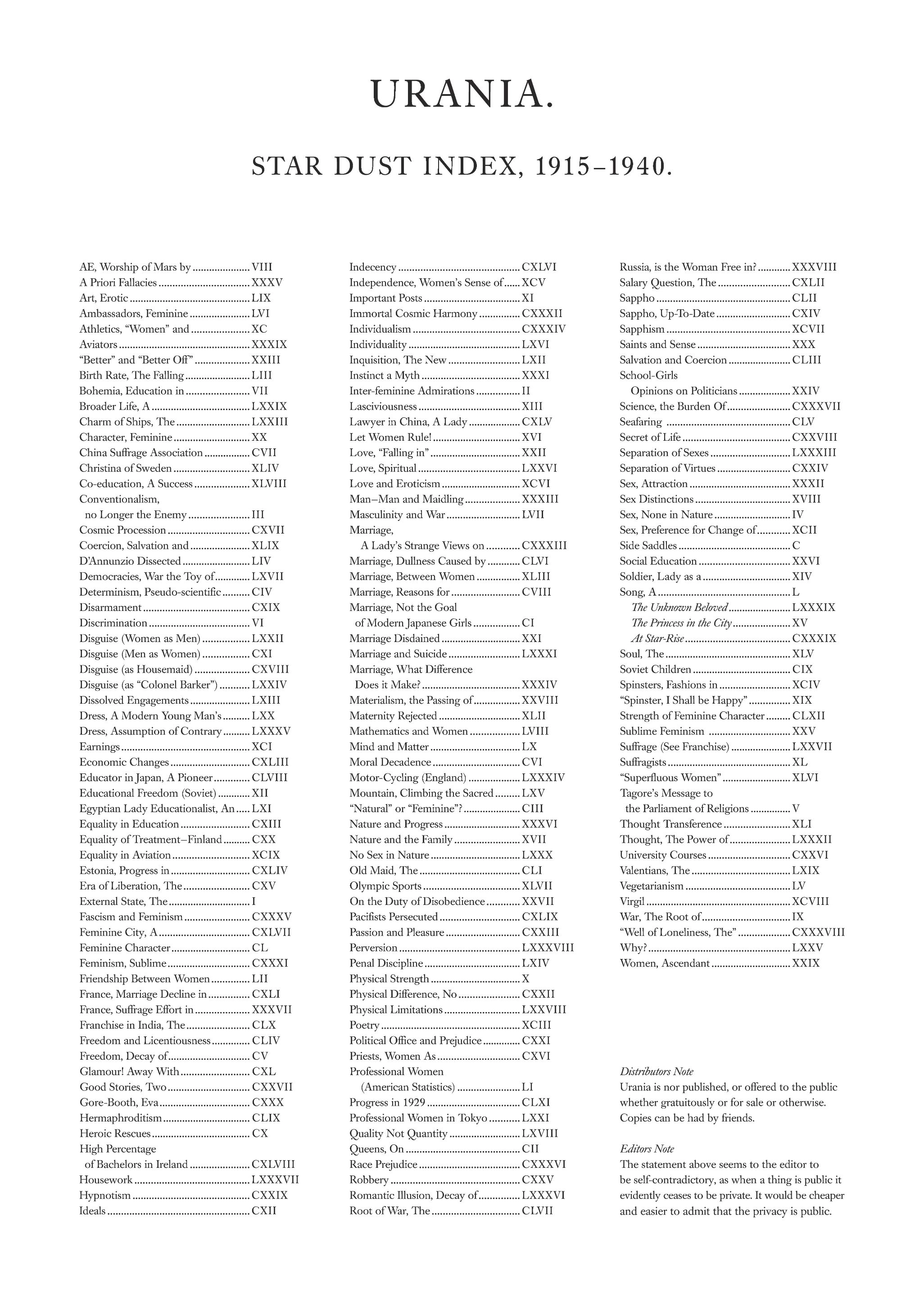

The exhibition focuses in part on the magazine Urania, which existed between 1915 and 1940 and was established by Esther Roper and Eva Gore-Booth – both campaigners for votes for women – along with Thomas Baty. The title Urania refers to a utopian place where there is no such thing as gender – at that time gays, lesbians and people who did not conform to gender norms often referred to themselves as Uranians. The magazine was distributed to ‘friends’ privately (presumably because of censorship laws) and has very little original or editorial content. Instead it comprises newspaper cuttings sent in by subscribers from around the world, which creates a kind of global index of instances of gender non-conformity, cross dressing, hermaphroditism, same-sex marriages and so on, as well as feminist activity. The magazine was produced by collective effort and seems to attempt to bring into being a new subjectivity as well as create networks of support and solidarity among people who would otherwise be invisible to each other.

ATP: ‘Many Maids Make Much Noise’ develops research that you started before this exhibition, on the history of the British Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU). Could you tell me where your interest in this topic comes from?

OP: I started researching the WSPU in 2010, when I was commissioned by The Women’s Library in London (in collaboration with Hester Reeve) to make a work in relation to their feminist history archive. We realised then that there is an incredible gap between the mainstream historical representation of the movement – as it exists in the media and what we were taught at school – and the complexity that we saw in the archival materials, letters, photos, and so on. Along with the struggle for the vote, the WSPU advocated for the opening up of education and professions to women and a large number of artists were among the members of the WSPU, the most prominent being Sylvia Pankhurst. Artists also played an important role within the wider women’s suffrage movement, for example in the Suffrage Atelier. This functioned as an alternative art school where people could learn how to work with printing processes, in order to produce visual propaganda for the cause. The artwork that Hester and I made as a response to the archival material was Open Letter to Tate Britain, demanding that the Tate address those artists who were a part of the suffragette movement, as they have largely been neglected by art historians – with the exception of Lisa Tickner in her book The Spectacle of Women (1988). Subsequently we ended up curating an exhibition of Pankhurst’s artworks at Tate Britain, under the name of The Emily Davison Lodge. This project follows on from that and addresses other aspects of the movement.

ATP: Why do you think it is important, today, to deal with a historical issue dating back a hundred years ago?

OP: Much of the work that I do as an artist is somehow part of and reflects on the struggle over how history is written. The exclusion of the suffragette artists from art history is a classic example of how female artists have rarely been considered important enough to be written about by art historians, which reflects society’s attitudes to women as a whole. In the example of the exhibition of Pankhurst’s artworks at Tate Britain, we wanted to make a feminist intervention in the canon of art history and also to open up a dialogue about the lack of representation of female artists, in both the historical and contemporary collection and exhibitions.

One of the posters I made for the exhibition at ar/ge kunst in Bolzano refers to Pankhurst’s anti-fascist activism on behalf of Ethiopia. She is well-recognised, especially in the British context, for her place in winning votes for women. However, less well-known is that she also fought against racism and imperialism. When Mussolini invaded Ethiopia in 1935, she was one of the few figures on the European left who associated this African struggle with the fight against fascism in Europe. In fact, she died in Ethiopia, having moved there towards the end of her life at the invitation of Haile Selassie. She also established the East London Federation of the Suffragettes (ELFS) in the poorest part of London and was later expelled from the WSPU, by her mother Emmeline and sister Christabel, because of her socialism. Subsequently the ELFS became the Workers Socialist Federation in 1918, the first communist party in England, briefly affiliated with the Third International. But she split from Lenin, arguing for the development of democracy within communism, and the reorganisation of domestic labour and representation of mothers through community-based soviets – in short a revolution in the family. Like many of the suffragettes she refused to marry and was critical of the manner in which marriage enshrined the inequality between the sexes in law. In fact, she had a child out of wedlock with her partner, an Italian anarchist named Silvio Corio.

For me she is one of the most appealing figures in that movement, as she was fighting for equality in a broad sense, not only linking class with issues of gender inequality, but also race, which feels very contemporary. The suffragette movement as a whole was not limited to the fight for the vote and was in many ways far more diverse than how it is perceived today. By revealing the complexity of that historical moment, and links to other social movements, its relevance to contemporary struggles becomes clearer. Women may have won the vote in this part of the world, but we still have not achieved much of what radicals like Pankhurst or the group connected to Urania were advocating. They mounted a challenge to a wide range of social norms that still exist today, including gender and the institution of the family.

ATP: How did you get to know about the magazine Urania? What struck you in this publication, so much that you decided to organise the entire structure of the show around it?

OP: In The Women’s Library archive I came across many photos of cross-dressing suffragettes, butch women, and stories of groups of women living together. I began to wonder about this and found out that many suffragettes were openly lesbian or gender non-conforming. They included the composer Ethel Smyth, Vera ‘Jack’ Holme – a frequent cross-dresser and chauffeur to Emmeline Pankhurst – as well as Eva Gore-Booth and Esther Roper – who certainly lived as a couple and were possibly in a trio with Christabel Pankhurst at one point. Through their behaviour, the WSPU were challenging traditional ideas of the family, as well as gender norms and it was what we would now think of as a very queer movement.

Much of what exists today of Urania is fragmentary and no complete run of the magazine seems to have been preserved. This intrigues me, as it turns Urania into more of a concept, an idea. It leaves some space for the imagination, which as an artist is not an obstacle as I can deal with historical material in a different way than a historian. At the beginning of every issue that I read at The Women’s Library, there was a statement:

To Our Friends – Urania denotes the company of those who are firmly determined to ignore the dual organization of humanity in all its manifestations. They are convinced that this duality has resulted in the formation of two warped and imperfect types. They are further convinced that in order to get rid of this state of things no measures of ‘emancipation’ or ‘equality’ will suffice, which do not begin by a complete refusal to recognize or tolerate the duality itself. If the world is to see sweetness and independence combined in the same individual, all recognition of that duality must be given up. For it inevitably brings in its train the suggestion of the conventional distortions of character which are based on it. There are no ‘men’ or ‘women’ in Urania.

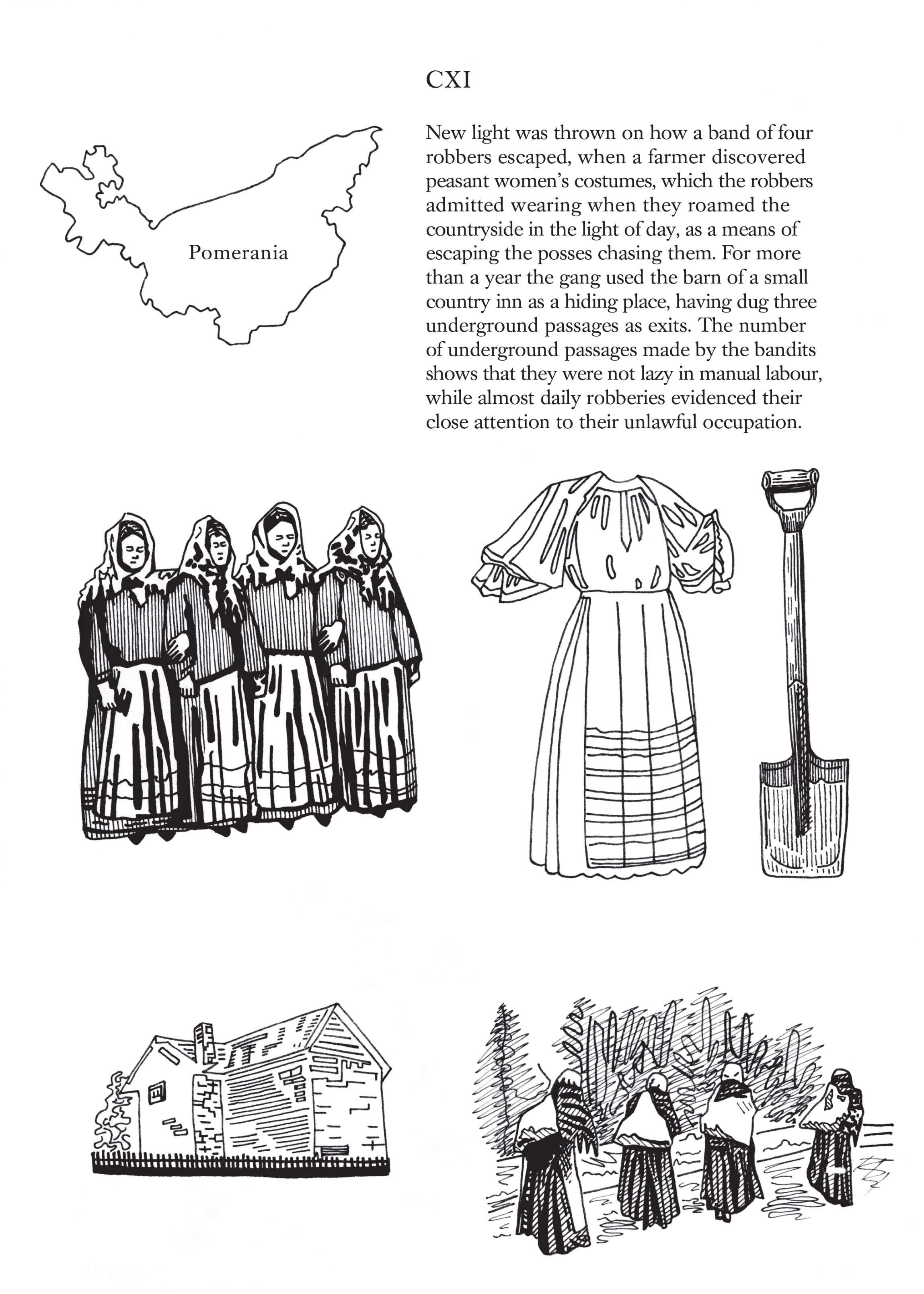

By challenging the very idea of a gender binary, they go beyond the rest of the feminist movement at that time. I used this statement in the exhibition, along with a series of posters I made, based on some of the articles that can be found in Urania: fragmentary stories about robbers in Pomerania who escape the law by disguising themselves as women; a man in Buenos Aires who upon his death is found to have been biologically a woman; plants which can change their gender, and so on. Another detail that is really fascinating to me about the magazine is that they were clearly anti-fascists and internationalists, and – contrary to my expectation – the magazine contains information about feminist movements around the world, in Japan, China, India, Egypt, etc., as well as other parts of Europe.

ATP: The title of the show ‘Many Maids Make Much Noise’ is an excerpt of a series of voice exercises that you carried out every day for a year to re-educate your voice after having lost it. How did you intertwine your personal history with political events tied to particular social events?

OP: Much of my work as an artist has been focused on the symbolic idea of ‘the voice’, on who is and isn’t able to claim the right to speak in public. When I lost my ability to speak for a whole year, after an illness in 2013, it profoundly changed the way I thought about that subject. Being literally voiceless, I felt vulnerable in public space and over the course of my treatment I was exposed to a lot of institutional settings, such as hospitals and the welfare system, which I then wanted to reflect upon. Within feminist thinking the ‘personal is political’, so these embodied experiences I had as an individual do, of course, point to wider structural problems.

In one of the works in the exhibition, titled Learning to Speak Sense, I worked with a voice coach who helped me to improvise around some of the voice exercises that I practised during that period. Many of the words, phrases and sentences that I was given as exercises by the hospital appear to me to have some kind of hidden political message. For example, the title of the show ‘Many Maids Make Much Noise’, or another phrase that I had to repeat ‘Militant Miners Means More Money’, both seem to speak about the power of the collective voice to be heard, demand attention, to ‘make noise’. In the British context, any reference to ‘militant miners’ immediately seems to indicate the miners’ strike of the 1980s, in which the National Union of Mineworkers took on Margaret Thatcher’s government in one of the longest strikes in British history. I became convinced that there is an anonymous author working as a care worker within the hospital system, who distributes their clandestine messages through the voices of individuals who are learning to speak. I find this idea very poetic.

However, I also wanted to explore the disciplining aspect of voice therapy, as its origins seem to be found in the training in rhetoric and elocution lessons of the nineteenth century, when men were taught to speak with authority and women in soft ‘pleasing’ voices. I have quite a low voice for a woman and when I was being treated in hospital I was encouraged to speak much higher. When I returned to that experience while working on this piece with the voice coach, we both questioned whether there had been any real physical reason for me to speak higher, or rather whether it was actually about convention. Therefore, in the sound piece we do a lot of work where I am trying to learn how to speak with a very deep male voice, which is traditionally what people associate with authoritative speech.

ATP: Do you think art can find its way into people’s conscience and change their minds about prejudices and false ideologies?

OP: I would question what you mean exactly by ‘art’, as it can be a slippery thing to define. In her book The Spectacle of Women, Lisa Tickner argues that ‘The art/propaganda divide is itself a kind of propaganda for art: it secures the category of art as something complex, humane and ideologically pure, through the operation of an alternative category of propaganda as that which is crude, institutional and partisan.’ To take the example of Sylvia Pankhurst: she is usually seen as having abandoned art for political action, however, this reiterates the conservative notion of art as a sphere separate from politics, and I would rather argue that she substituted one form of representation for another. Once she had become a full-time political campaigner she continued to produce visual propaganda for the movement, established a co-operative toy factory in London’s East End with toys designed by artists, turned to writing political plays, fiction and history and even towards the end of her life was involved in the art scene in Ethiopia.

During the struggle for votes for women in the UK, all the women’s suffrage organisations involved, including the non-militant ones, were profoundly aware of the power of images, posters, graphic design, art, large-scale public spectacles, and of the importance of changing the representation of women. They saw this as very much part of the struggle for the vote and the newspaper produced by the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies, called The Common Cause, called on activists to ‘agitate by symbol’. This kind of activity by artists, along with work more recognisable within traditional definitions of art – such as Pankhurst’s The Women Workers series of paintings from 1907, which document women’s working conditions – present clear examples of how art can play a role within political movements.

ATP: In my personal opinion I don’t think art can ‘make noise’, but I think that art can question things and help crush certainties. Ideally, what do you wish to achieve with your works, on a political and social level?

OP: Working within institutional settings can be a way of challenging the practices of museums and galleries as part of the struggle over representation and how history is written. History is a very normative discipline. What we think we know of our history shapes our world today, our idea of who we are, the actions of our governments, foreign policy, and so on. Art is no substitute for activism, but representation does matter, images and symbols do have some power to shape our perceptions. For me art is about distributing ideas, drawing attention to certain neglected historical details, micro-histories, making the story more complex in opposition to the usual simplified and monolithic versions of history that are used to prop up bad politics.

20 January 2016

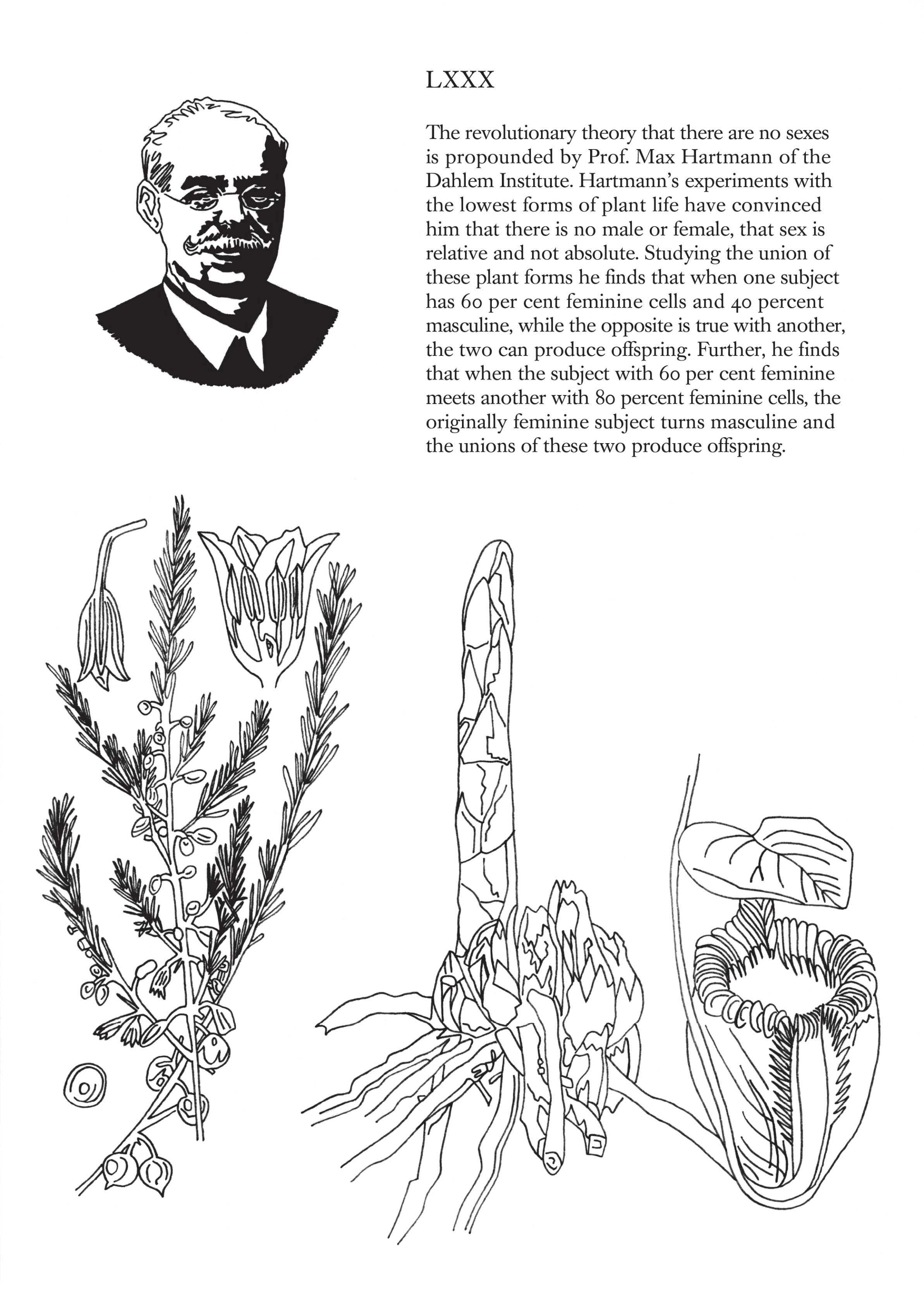

Urania: LXXX No Sex in Nature, 2015

off-set litho poster, 59.4 x 84.1 cm

Urania, 2015

series of posters

Urania was a journal published between 1915 and 1940. It was founded by a lesbian couple who were active suffragists, Esther Roper and Eva Gore-Booth, along with Thomas Baty (whose nom de plume was Irene Clyde). The name Urania refers to a specific idea of Utopia, as a place where the categories of ‘male’ and ‘female’ do not exist. In the early twentieth century those who did not neatly conform to social and sexual norms constructed around ideas of ‘male’ and ‘female’ behaviour, often referred to themselves as Uranians. The journal Urania was a kind of catalogue of incidents of gender troubling and feminist struggles; a collection of articles clipped out of newspapers from around the world that were re-published with very few editorial interventions, and distributed privately to a wide network of friends and supporters. Articles were often unsigned or published under a pseudonym used by several writers, which made Urania into an ‘institution’ that constituted itself through the voice of a collective. The little-known magazine was not illustrated, so this series of nine posters is an attempt to create a visual index of their interests.

Urania: Star Dust Index, 2015

off-set litho poster, 59.4 x 84.1 cm

Urania: CXI Disguise (Men as Women), 2015

off-set litho poster, 59.4 x 84.1 cm

Further Reading

Olivia Plender in conversation with Elena Bordignon about ‘Many Maids Make Much Noise’ at ar/ge kunst, Bolzano, 2015

(download)‘Many Maids Make Much Noise’, ar/ge kunst, Bolzano, 2015

(view here)