‘Sylvia Pankhurst’, Tate Britain, 2013, installation view

‘Sylvia Pankhurst’, 2013-14

display of artworks by Sylvia Pankhurst, Tate Britain, London, curated by The Emily Davison Lodge (Olivia Plender and Hester Reeve), in collaboration with Emma Chambers

In 2010 The Emily Davison Lodge – Olivia Plender and Hester Reeve – sent a letter to Tate Britain, demanding that the museum acknowledge Sylvia Pankhurst and the other neglected female artists who had been part of the suffragette movement. Pankhurst’s name is well-documented in social and political history on account of her activism, and in particular her involvement with the campaign to win votes for women in the UK via the establishment of the Women’s Social & Political Union (WSPU) in 1903. Less celebrated, however, is that Pankhurst was also a highly skilled, versatile and pioneering artist in her own right, who trained at the Manchester School of Art and then the Royal College of Art in London.

Sylvia Pankhurst, Inside a Boot Factory: Fitters at Work, 1907

gouache on paper

The exhibition included paintings and drawings from a series titled The Women Workers (1907). These artworks were made on a tour of Britain that Pankhurst undertook in order to document the poor working conditions women were forced to endure in fields and factories. They originally accompanied journalistic articles by Pankhurst, in publications such as The London Magazine in November 1908, describing how working-class women were trapped in unskilled, low-paid and dangerous work, and laying out arguments for pay equality with men.

Sylvia Pankhurst, In a Glasgow Cotton Mill: Minding a Pair of Fine Frames, 1907

gouache on paper

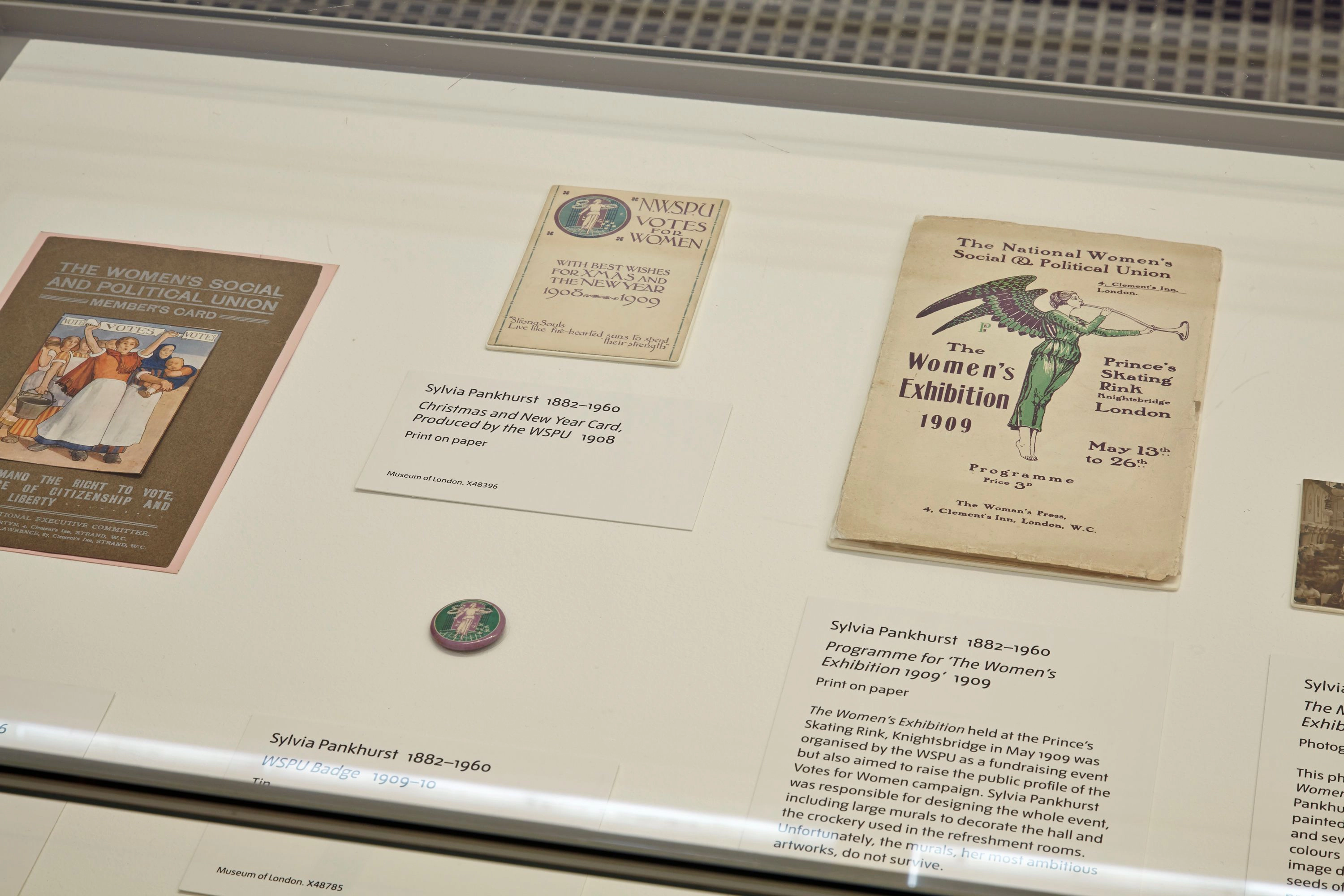

Shown alongside the paintings were examples of the Arts and Crafts influenced ‘angel of freedom’ logo, designed by Pankhurst for the WSPU and which appears on banners, a tea set sold to raise funds for the movement, as well as a certificate designed by Pankhurst and signed by the leaders of the WSPU. This was routinely awarded to suffragettes who had spent time in prison for the cause, along with the portcullis broach, which Pankhurst based on the gates of HM Prison Holloway, where she and many other suffragettes were incarcerated.

‘Sylvia Pankhurst’, Tate Britain, 2013, installation view

‘Sylvia Pankhurst’, Tate Britain, 2013, installation view

Framing the exhibition was the Open Letter to Tate Britain (2010), signed by The Emily Davison Lodge. The original lodge was established shortly after the death of the celebrated suffragette Emily Wilding Davison by her friends Marie Leigh and Edith New in 1913, in order to ‘perpetuate the memory of a gallant woman by gathering together women of progressive thought and aspiration, with the purpose of working for the progress of women according to the needs of the hour.’ The letter was a feminist intervention in the canon, demanding that museums such as Tate address the ongoing exclusion of female artists from art history.

In 2018 Tate Britain announced that they would be purchasing four of the paintings from The Women Workers (1907) series, which had been a part of the exhibition.

To: Head of Collections

Tate Britain

Millbank

London SW1P 4RG

May 13th 2010

Dear Ann Gallagher,

We are writing to you to request an appointment to discuss the establishment of a gallery room at Tate Britain, devoted to the work of the British artist Sylvia Pankhurst.

Sylvia Pankhurst’s name is well-documented within social and political history, on account of her celebrated mother and family’s campaign for female suffrage via the establishment of the Women’s Social & Political Union (WSPU) in 1903. But less celebrated is how, aside from being a leading figure of the campaign to win women the vote in this country, Sylvia Pankhurst was also a highly skilled, versatile and pioneering artist in her own right. Through our recent research into her work, we are saddened by the lack of recognition accorded her as an artist and the ongoing pervasive attitudes within society and the arts that such an omission might stand for. Tate Britain currently has no works by Sylvia Pankhurst in the collection and seems to have omitted specific recognition of any feminist impact upon art history, in its thematic arrangements of British art 1700-present date, despite counterculture and rebel voices having always played a serious role in the formation of British culture.

Sylvia Pankhurst’s practice ranged from drawing to painting, from fine art to craft, suffragette propaganda, banner and movement identity design to public speaking, writing and political activism. In our time, when any singular narrative of the traditional argument of art versus life has expanded beyond any neat categorisation of either, the practice of Sylvia Pankhurst forms the basis for renewed discussion on art’s relationship to ‘change’ – do we in the art world know how to value ‘deeds not words’ in 2010? The suffragette insistence on Deeds Not Words, carried through seventy years later to the women’s lib claim that the personal is political, seems ready for a third stage of reappraisal, in the ongoing fight to realise equality for women, and the representation of female artists within the canon of art history.

Some further historical facts to back up our proposal to accord Sylvia Pankhurst her due place in British art history:

She studied at Manchester Municipal School of Art and then went on to win a scholarship at the Royal College of Art (she was later to challenge them on their prejudice against women artists). Her practice expanded upon becoming a WSPU leader; she designed banners and logos (most notably the ‘angel of freedom’, which featured on badges, tea pots and the front page of Votes For Women, the suffragette newspaper). It is claimed that this is the first instance of a campaigning organisation deliberately using design and colour to present an ‘identity’. Of particular note are her Holloway Broach (1909), a silver design incorporating the portcullis and arrowhead of freedom that was awarded to WSPU suffragettes who had been imprisoned for their actions, and the huge 20-feet banners she designed for the famous fundraising Suffragette Exhibition at the Princes Skating Rink in 1909.

An active militant, Sylvia Pankhurst was involved in some of the key moments of the WSPU campaign. Before the avant-gardes had ripped up their first canvas, she was one of the first to attack an artwork, recognising its status as a symbol of patriarchal power and ‘the secret idol of capitalism’. Other artists of the time acknowledged the power of these actions: for example, Wyndham Lewis gave the movement his blessing in the publication Blast, with the words ‘We admire your energy. You and artists are the only things... left in England with a little life left in them.’

Sylvia Pankhurst was imprisoned many times for her actions. While in Holloway Prison she went on hunger strike alongside other suffragettes, suffered force-feeding and yet also made sketches of prison life so she could publicise the adverse conditions to the outside world. The Penal Reform Union was in fact formed at one of the breakfast-welcomes held upon her release from jail. She also produced one of the first historical overviews of the campaign, The Suffragette: The History of the Women’s Militant Suffragette Movement 1905-10, published in 1911 and later, in 1931, one of the most notable accounts in existence, The Suffragette Movement.

Aside from the art and activism, Sylvia Pankhurst’s particular contribution to the historical force of the suffragette movement was to encourage working women and the poor to take power – depicting a mill woman and a washer woman, for example, on the suffragette members’ card that she designed in 1905. Indeed, her own criticism of the WSPU was that it was too bourgeois, and in 1913 she officially broke ties and founded the East London Federation of the Suffragettes (ELFS), which later became the Workers’ Socialist Federation. Here she worked with people from all strata of society and allowed men to join in the cause:

'I was looking to the future; I wanted to rouse these women of the submerged mass to be, not merely an argument of more fortunate people, but to be fighters on their own account, despising mere platitudes and catch-cries, revolting against the hideous conditions about them, demanding for themselves and their families a full share in the benefits of civilisation and progress.' (The Suffragette Movement, pp. 416-17)

Sylvia Pankhurst always displayed a heightened awareness about the complexities of practising as an artist and yet simultaneously wishing to be of service to society. She wanted to put her art at the service of the poor and yet to fund herself as an artist meant dependence on bourgeois patrons. She questioned, ‘whether it was worthwhile to fight one’s individual struggle... to make one’s way as an artist, to bring out of oneself the best possible, and to induce the world to accept one’s creations, and give one in return one’s daily bread, when all the time the real struggles to better the world for humanity demand another service.’

These conflicts provide a radical backdrop to her ‘representational’ works created when she toured the country making drawings of working-class women in their various places of labour. Some commentators have claimed that a crucial turning point in the Liberal PM Lord Asquith’s antipathy for the women’s vote was when he realised, through Sylvia Pankhurst work and campaigning, just how many British women constituted the nation’s workforce. For all the passion dedicated to political and social reform, Sylvia Pankhurst never faltered to declare that art was her ‘chosen mission... which gave me satisfaction and pleasure found in nothing else.’ (The Suffragette Movement, p. 428)

Pankhurst continued throughout her life to engage with art and politics. She was later close to the leaders of the Pan-African movement and campaigned for the independence of Ethiopia, against Mussolini. She subsequently settled there and is still recognised today by the Ethiopian art world as a serious cultural figure.

We bring these biographical facts to your attention, not just to impress upon you Sylvia Pankhurst’s importance, but to again link such a significant life’s work to the advent of British modern art. She stands as a radical forerunner to the later aims of the European avant-garde; indeed this fact can be backed up by the Italian Futurist Marinetti’s claim that ‘In this campaign for liberation, our best allies are the Suffragettes’ (from Le Futurisme, 1911).

For all of the above, we have nonetheless found no instances of Sylvia Pankhurst being included in books on the relation between art and politics and rarely does one find texts mentioning her art practice on art book shelves, The Women’s Library in London excepting. Ultimately, the great radical nature of her achievement lies in the combination of art and activism. Like her fellow militant suffragettes, Sylvia Pankhurst did not just fight for the vote; she fought for the creation of new forms of political life. Having said ‘I would like to be remembered as a citizen of the world’, she fought for freedom not only for women in Britain, but also for women around the globe. Ironically, she remains an uncelebrated figure within British art, despite contemporary expanded definitions of art and interest in its social agency.

We look forward to a discussion of our request that Tate Britain purchase works by Sylvia Pankhurst.

Yours sincerely,

Olivia Plender & Hester Reeve

The Emily Davison Lodge

c/o The Women’s Library

London Metropolitan University

25 Old Castle Street

London E1 7NT

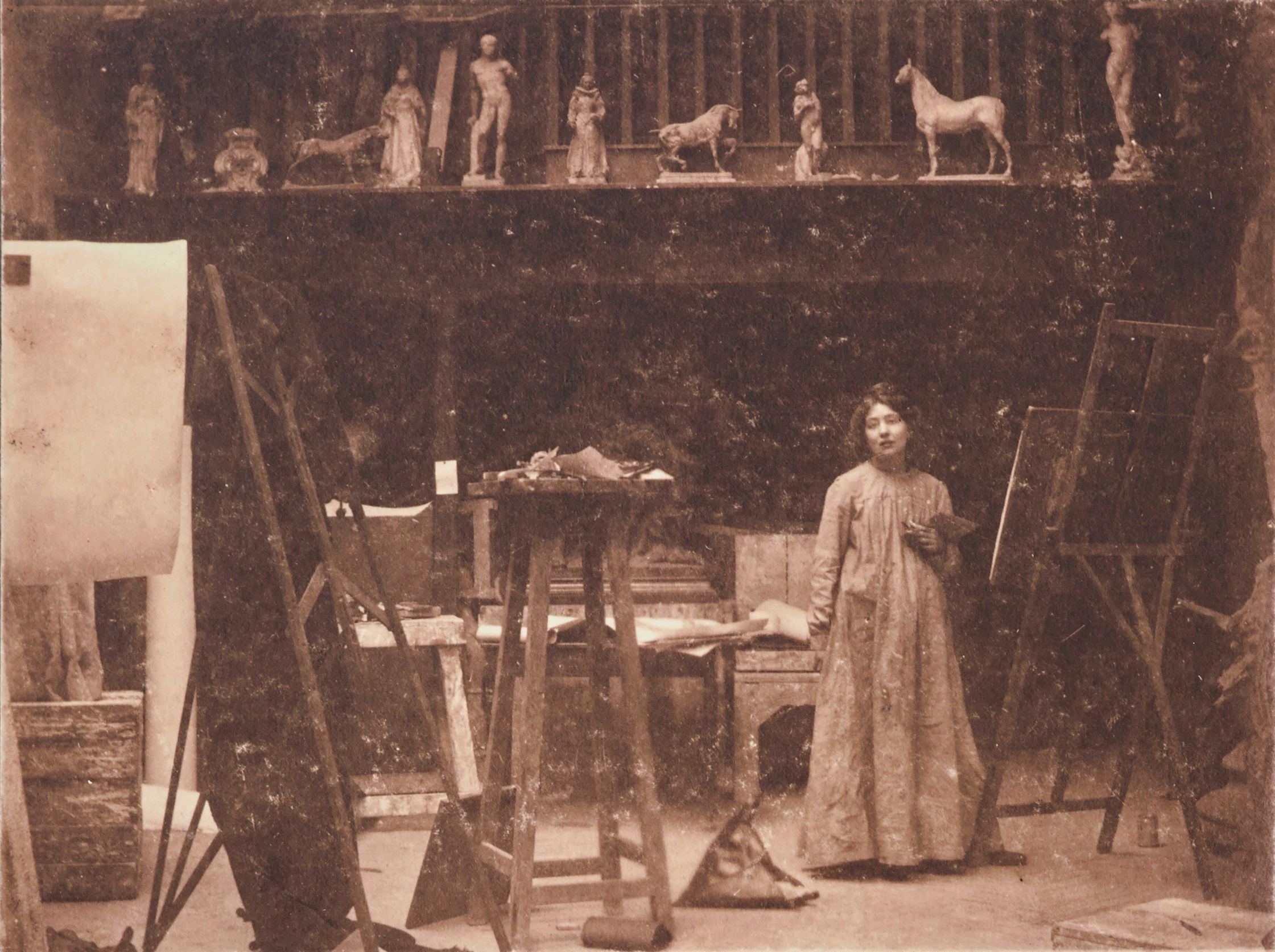

Sylvia Pankhurst in Her Studio, circa 1907, photographer unknown

Further Reading

‘Learning and Playing’, Catherine Grant, published in Feminism and Art History Now: Radical Critiques of Theory and Practice, edited by Victoria Horne and Lara Perry (London: IB Tauris, 2017)

(download)Feminism and Art History Now: Radical Critiques of Theory and Practice, edited by Victoria Horne and Lara Perry (London: IB Tauris, 2017)

(view here)‘Sylvia Pankhurst’, Tate Britain, London, 2013-14

(view here)The Guardian, ‘Sylvia Pankhurst paintings of women at work acquired by Tate’, 20 December 2018

(view here)