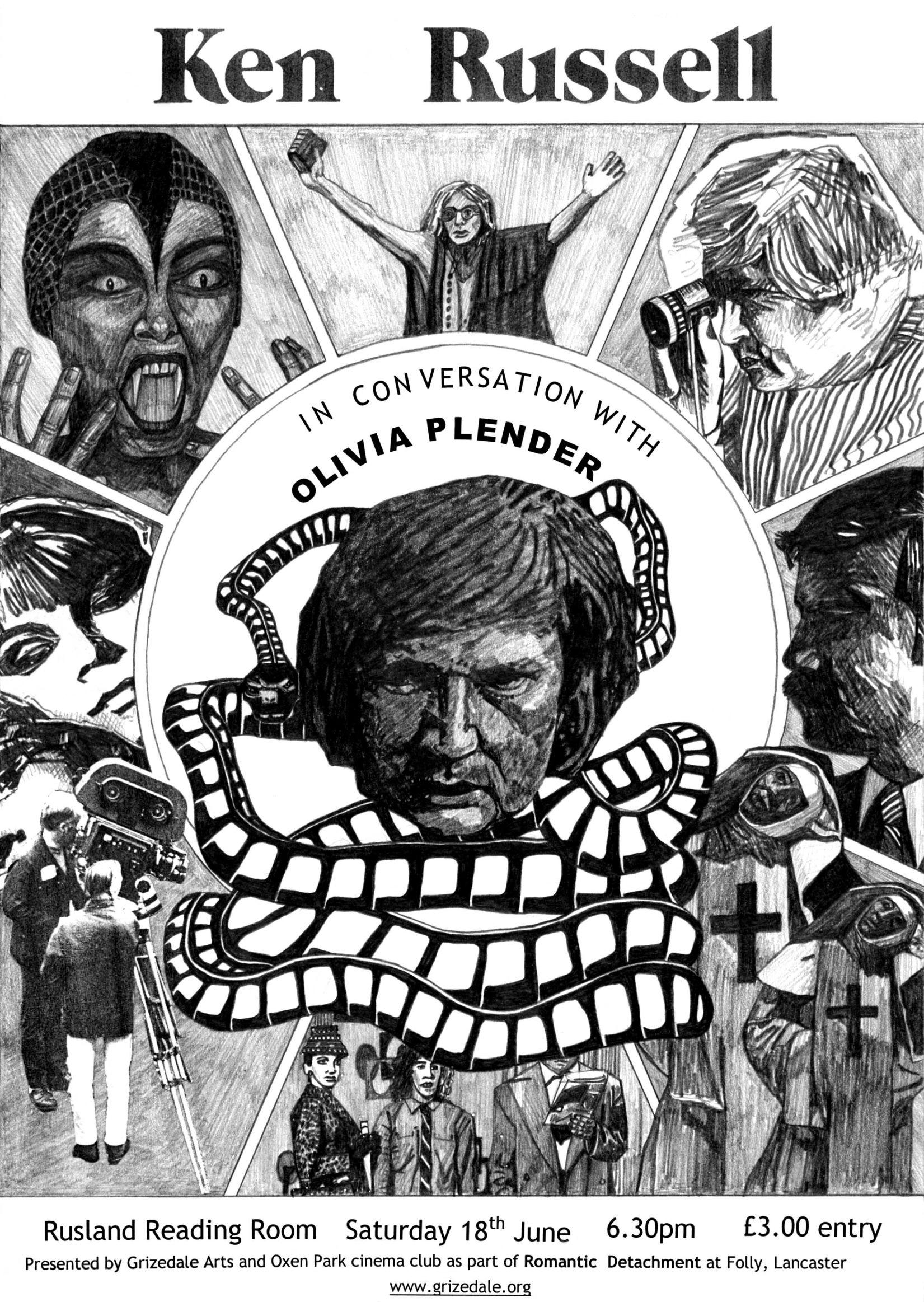

Ken Russell in Conversation with Olivia Plender, 2005, performance, commissioned by Grizedale Arts

Ken Russell in Conversation with Olivia Plender, 2005

performance, commissioned by Grizedale Arts for the exhibition ‘Romantic Detachment’, MoMA PS1, New York, and Folly Gallery, Lancaster

In this performance I interviewed the notorious film-maker Ken Russell, in front of an audience comprising members of a local cinema club, in a village hall in rural Cumbria. The performance took place in a set that recalls television studios of the 1970s, when Russell was at the height of his fame as a film director. Mimicking the tone of BBC interviews from that time, I attempted to speak with authority as if I were a professional presenter. The audience watched me – a young female interviewer performing a role that is traditionally embodied as male – as I wrestled for power over the conversation with the elderly director, who was apparently in his natural habitat.

Ken Russell in conversation with Olivia Plender

Ken Russell has often been referred to as the enfant terrible of British cinema and was lauded and vilified in equal measure for films such as Women in Love (1969), The Devils (1971), Tommy (1975), Altered States (1980) and The Lair of the White Worm (1988). However, he began his film-making career by making biographical documentaries about artists, writers and composers for Monitor, the BBC’s original arts programme, now considered to be one of the high points of British television history and a training ground for film-makers (most famously Russell and John Schlesinger). More recently, Russell is by his own admission considered ‘un-bankable’ by the film industry, but as ever unstoppable, he has returned to making amateur films with a video camera in his own back garden. He is currently working on a film about Aleister Crowley. Many of Ken Russell’s early documentaries and films were made in England’s Lake District, an area associated with the Romantic movement where he was a one-time resident. I met him in 2005 at the Rusland Reading Room in the heart of ‘Wordsworth country’. In front of an audience of members of the local Oxen Park cinema club, we spoke about documentary making, his controversial career and whether – in the words of Dilys Powell, former Sunday Times film critic – ‘the talent is there in him alright but it’s an appalling talent.’

Olivia Plender: How did you start making films?

Ken Russell: I tried to get into the film industry when I was in my teens, but unless you knew somebody in the industry already you didn’t stand a chance. You couldn’t get past the studio gates even. But by the time I’d done a variety of things, from ballet dancing, acting and photography to cinematography… and finally applied to the BBC for a job as a film director, all the studios that had turned me away were owned by the BBC and doing television. They wanted new talent.

OP: Why did you start making films about artists? Was it because of the format of the programme?

KR: I started by making amateur movies with family and friends. I did one documentary on Lourdes, when I was converted to Catholicism. And then I did a film that was rather like the Jean Cocteau movie Beauty and the Beast (1946). It was called Amelia and the Angel (1957) and was about a little girl in a school nativity play, who takes her wings home after a rehearsal to show her mum, and then her brother breaks them. She has 24 hours to find another pair of angel wings in London before the performance. That was one of the films I submitted to the BBC. It was a very sought-after job. Dozens of people submitted films and 99 per cent of them were about barrow boys at the Elephant and Castle. Mine was the only fantasy. Out of sheer desperation, Huw Weldon [the editor of the programme] took me on. He was my mentor… Huw also influenced people like Melvyn Bragg, half a dozen brilliant stage producers, film producers and musicians.

When I joined Monitor, it was a 45-minute magazine programme. It was on every Sunday night after the feature film, at 9.30 pm. When you see arts programmes now, they’re usually on at 2 am, because they’re not very popular. But Huw really encouraged the producers to express themselves and concentrate on subjects that they were mad about. I was mad about music, so I was encouraged to make films about composers.

OP: Of the programmes that you made for Monitor, the film on Elgar (1962) was the most popular. However, you said retrospectively that your representation of Elgar was too romantic, too much of a PR job, in direct contrast with Delius: Song of Summer (1968), the biopic that you made about the composer Frederick Delius. The latter film abandoned the documentary style entirely and dramatised Delius’s dominating relationship with the young composer Eric Fenby.

KR: I had done many films in between and Huw Weldon would always say, ‘We want facts’. The first film I made on a composer was about Prokofiev, so I said to Huw, ‘Can I have an actor?’ ‘An actor playing him? But he’s dead, isn’t he? No, you can’t have an actor. That’s madness.’ And I said, ‘What if I had a pond and you see the reflection of a man?’

OP: Was that somehow permitted within Weldon’s very strict idea of what documentary should be?

KR: He said, ‘Well maybe, as long as it’s a muddy pond and you stir it with a stick to get the reflection all broken up.’ By the time we got to Elgar, he allowed me to have seven people impersonating Elgar, from a little boy to an old man, as long as they were in long shot.

OP: In your biographical films about artists and composers you increasingly introduced semi-fictionalised ‘visionary’ scenes; such as the sequence in Mahler (1974) in which the composer undergoes symbolic religious conversion on a mountainside, at the hands of Cosima Wagner wearing a Nazi uniform. Do you see yourself as a visionary?

KR: Well it’s the visual equivalent of a conductor. I can play a Bernstein record of Mahler or I can play a Klaus Tennstedt version, and then you’d think it was almost a different composer. I had a sequence in Mahler where he imagines himself being burned by the Gestapo. He died in 1910 and the Gestapo didn’t come along until much later, so I was accused of fantasy and all the usual embarrassing stuff. Then I discovered that one of the greatest conductors of Mahler was looking for me. I thought he wanted to kill me, but when he [Tennstedt] finally tracked me down he invited me for an audience. He said, ‘That scene where you have Mahler being burned by the Gestapo… it’s exactly what I think of when I’m conducting the Sixth Symphony.’

OP: Within the British context you have been criticised for taking those leaps of fantasy and not conforming to the conventions of realist cinema…

KR: But I’m not interested in realist cinema. There are plenty of people doing realist cinema. And I’ve often been accused of being operatic. Well England’s the only country in the world where operatic is a dirty word. I think some of the most powerful scenes in my films have been just the music and the image. I don’t know if you’ve had the good fortune of attending a silent film with an orchestra playing? Well the impact is indescribable: that’s how movies were born.

In the 1920s some of the greatest films were made by Germans. During the war I had a little hand-cranked projector, and the library where I used to go only had German Expressionist films. I had one gramophone record, on one side it had a march by Arthur Bliss from a marvellous English sci-fi movie called Things to Come (1936) and on the reverse it had a march by Grieg. The two things that I played most, in my Dad’s cinema raising money for the spitfire fund, were Fritz Lang’s Siegfried (1924) and his Metropolis (1927). I found that the Grieg march fitted and brought the picture alive and when I played Metropolis, the march from the English sci-fi movie brought that alive. From the age of ten or eleven, I knew the power of music and image and that’s always stayed with me.

OP: Throughout your films you’ve introduced references to popular culture. In Women in Love Ursula sings the tune I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles and you situate D.H. Lawrence’s metaphysical characters in relation to the everyday world and popular material. Do you think that is an important tendency within your work?

KR: I do. We’re all living mixed up in popular culture, for better or for worse. I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles was written the same year that Lawrence wrote Women in Love (1920) and he may have heard it. He wasn’t against popular culture. He often went to movies. For me I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles represents the 1920s era of fantasy and dreams just blowing away, popping like bubbles. The girls in the story have a romantic notion of love, the men do as well, and it turns out in the end to be just bubbles.

OP: A lot of the criticism directed against your films – particularly in the 1970s by Alexander Walker [Evening Standard film critic] and Dilys Powell – seems to be about that ‘vulgar’ popular material. Do you have a fascination with vulgarity?

KR: In a film I did on myself, in which my four-and-a-half-year-old son played me aged 55, there’s a sequence when his wife (played by my six-year-old daughter) reads out a whole lot of arbitrary horrible criticism, ‘A fiend of the senses’, degrading, desolate, horrible reviews. He’s looking through a whole sheaf of photographs of his films. He’s so depressed that he gets up to throw them into the fire and she says, ‘Hey, they’re not about you, they’re about Debussy.’ We all know Debussy, one of the great geniuses of music, but in his time these were the opinions of so-called music critics. Well they [the critics] lie. Barry Norman [the former BBC film critic] gave The Lair of the White Worm – probably one of the funniest horror films ever made – a terrible review. He hates films.

OP: Is there a degree of satire in what you are doing? In The Lair of the White Worm are you satirising the horror genre?

KR: Yes, in a way, its tongue in cheek. The hero [Hugh Grant] is supposed to be Prince Charles. There’s something unique about that film that nobody has ever discovered (maybe it’s not worth discovering). The film is like a snake. Each cut is linked to the next cut, like a snake, a continuous form and it’s either joined to it visually – so you’ll see a car leaving one scene driving into the next – or you will hear a unique sound in one scene and it carries into the next. The whole thing has a form.

OP: Do you think the horror genre can contain ‘vulgarity’ better than the high cultural film product?

KR: I think anything is fair game if you know how to do it. Horror is probably the easiest genre. Recently I was doing a film for the BBC, in which a lot took place in Southampton (where I was born), at the Broadway cinema where I spent the formative years of my childhood. I told them about a film I saw in 1935 – now I am sort of parodying it – called The Secret of the Loch (1934). It was about the Loch Ness monster. I was five years old and I’d been taken to the cinema. I knew that I would eventually see the monster. There was a sort of cave – actually a cracked flowerpot – that the monster would come out of. When he finally did, I totally freaked out. Do you know what the monster looked like? What is the most horrifying image of a monster you can imagine? It was a plucked chicken. Can you imagine anything more horrific? Anyway, I saw it again recently and it wasn’t a plucked chicken at all. It was an iguana. But who’s seen an iguana when you’re five years old?

OP: In many of your films there is a parallel between a human body and a dead body. Physicality is quite disgusting, especially in The Devils and Women in Love, where you cut from a sex scene to two drowned bodies in the lake.

KR: Well it’s life and death. The events in The Devils did take place, according to Aldous Huxley, at the height of the plague in Loudon [in medieval France]. There was death everywhere. They’d be burning people at the stake one day and then they were shovelling bodies into a pit. Life was cheap and it was all mixed up together. People were killed at the drop of a hat. Death was no stranger to the people of the city. So, if I hadn’t mixed them up it wouldn’t have been a true picture.

OP: It seems part of a recurring assault on the idea of the autonomous or ‘true’ self and a step towards postmodernity. An early example of postmodernity in your work appears in Dante’s Inferno (1967) – a Monitor film about Dante Gabriel Rossetti and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. The costumes and settings are all historically accurate, however, one character breaks the linear historical narrative for a split second by throwing a yo-yo.

KR: That’s a deliberate ploy to start you thinking, because it’s only a film and what is real? It’s only an opinion.

OP: Can you tell me a bit about the process of making your most recent film The Fall of the Louse of Usher (2001), and how it came about?

KR: It’s a compendium of several tales of mystery and imagination by Edgar Allan Poe. I tried for ten years to get it set up as a feature film, but there were always too many hang-ups. They [the studios] wanted the actors I didn’t want, or they wanted a pop group. Also, I wanted to find out whether it’s possible to make a film in the garden with friends. I’m not sure it was, to be perfectly honest.

OP: The Fall of the Louse of Usher is full of references to your previous films; for example, the scene in which Roderick Usher is wearing a bird mask surrounded by nuns seems to mirror the sequence in The Devils in which the protestants, dressed as black birds, are being shot.

KR: I guess I’m scraping the barrel.

OP: I was wondering whether it was a conscious deconstruction of your own oeuvre?

KR: Well there’s a subconscious element, I suppose…

OP: Do you always work with the same troupe of actors?

KR: Especially these days… my wife, myself and the man up the road.

OP: But even in the 1960s, Oliver Reed appeared in most of your films, or Christopher Gable…

KR: Or someone like Murray Melvin, who’s lesser known. He was a debauched priest in The Devils and a dancer in The Boyfriend (1971). For a long time, I considered it to be like a travelling show. I took my family around and you could see my five children (the first five) growing up in all the films. Ingmar Bergman made a very good film that I have never seen reissued, called Sawdust and Tinsel (1953). It’s about a group of players going around putting on a show. With these little films I’m making in my back garden, I’m still doing the same thing.

OP: Is it important that people see them or is it more about the process of film-making?

KR: Yes, I hope they do get a showing. I still hope they have a life in one form or another.

Ken Russell in Conversation with Olivia Plender, 2005, printed poster, 42 x 59 cm, commissioned by Grizedale Arts

Further Information

‘Romantic Detachment’, Ken Russell & Olivia Plender In Conversation, Grizedale Arts, 2005

(view here)