Blind Eye, 2013, video, 6 min. 51 sec., still

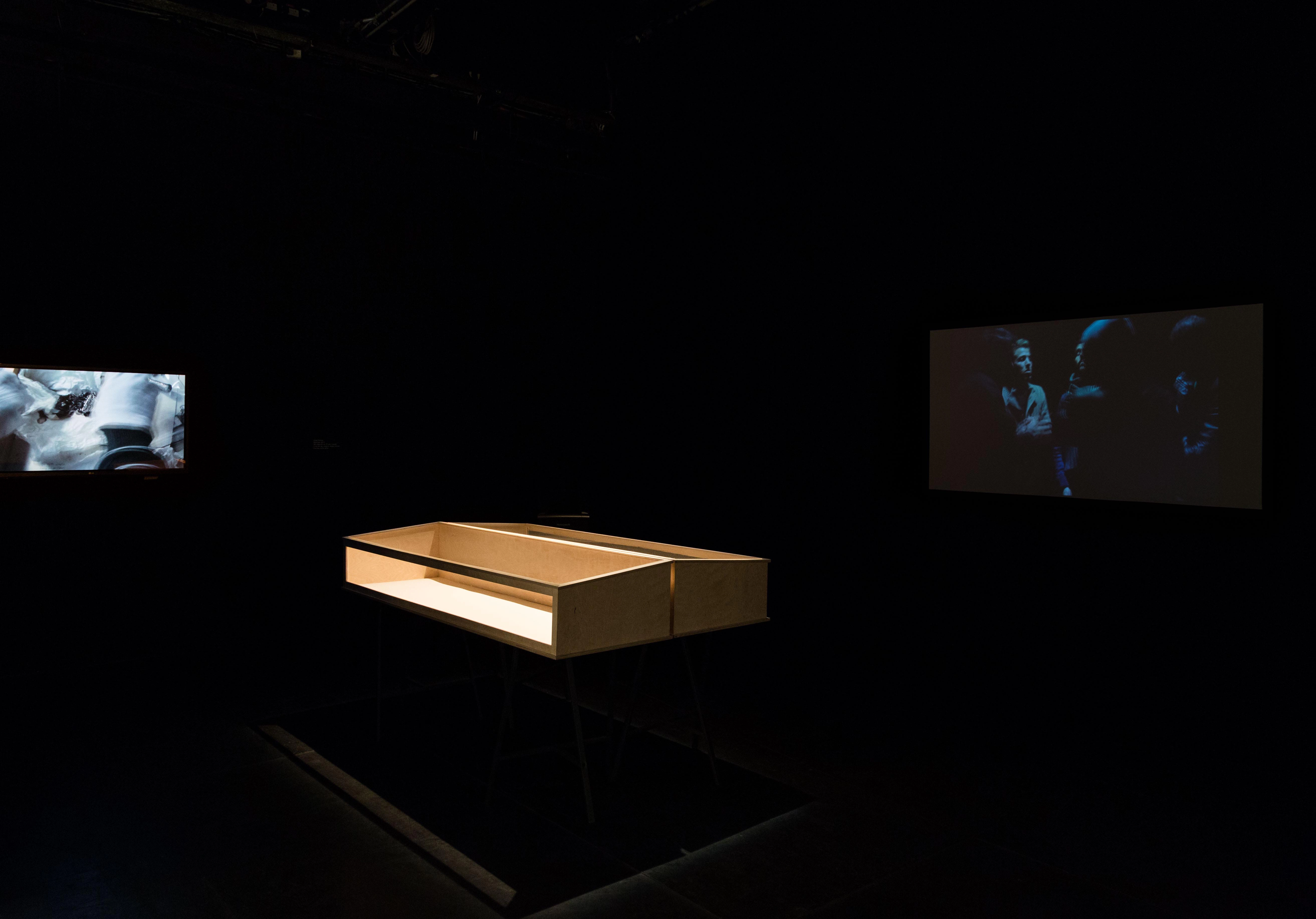

Blind Eye, 2013, video installation with empty vitrine, ‘Points of Departure’, Institute of Contemporary Arts, London

Blind Eye, 2013

video installation, ‘Points of Departure’, Institute of Contemporary Arts, London

This series of artworks comprises a video, an empty vitrine and a publication, made during a residency at Art School Palestine, Ramallah, in 2012 and 2013.

Blind Eye, 2013, video, 6 min. 51 sec., still

The viewer enters the space and hears a voice describing a collection of magical amulets, which was assembled by Tawfiq Canaan, a Palestinian doctor and amateur ethnographer based in Jerusalem, in the decades before 1948 and the Nakba. From time to time we glimpse a pair of white-gloved hands carefully showing one of the shiny amulets to the camera, as Baha Jubeh, the collection’s curator, tells us each object’s story. Canaan documented the folk healing practices of Palestinian villages, because he found that it was necessary to understand people’s beliefs in order to treat them successfully. The curator describes the danger attributed to the act of looking and how envy is deflected by the amulets as they dazzle the eye. But the inaccessibility of the image highlights the fragility of the collection, as he struggles to preserve the history of these now anonymous villagers, as did Canaan and his family after the Nakba.

Blind Eye, 2013, video, 6 min. 51 sec., still

This is one of the few collections held in the occupied West Bank, in contrast to the hundreds of museums scattered throughout Israel. They tell a contradictory version of history in which Palestine is represented as having been terra nullius prior to 1948.

Blind Eye, video, 6 min. 51 sec.

Olivia Plender in conversation with Baha Jubeh, a Palestinian Curator and ethnographer, responsible for the Tawfik Canaan Collection of Palestinian Amulets, held at Birzeit University, Palestine.

Olivia Plender: Can you begin by telling me about the collection itself?

Baha Jubeh: People usually think of amulets as triangle shapes. We have a lot of categories in the collection, which can be classified: jewellery, pilgrim’s certificates, paper talismans, beads, bones, organic material like garlic, the head of a small snake… They would roll a Quranic inscription or magic talisman and place them in a container, in order to wear it as jewellery on their dresses. These are rooster eyes, originally from Hebron. And there are other eyes, which are bigger like the camel eye. They are for protection against the evil eye. Canaan studied all these objects. He would ask each patient why he or she used to wear this amulet and he would then write about it.

OP: Who was Canaan?

BJ: Canaan was a medical doctor. He was born in Beit Jala in 1882 and died in 1964. He studied medicine in Beirut. Once he came back to Palestine he became very interested in folk beliefs and medicine. He believed there was a relationship between the beliefs of the people and some of the sicknesses; so he started this collection and gathered more than 1400 pieces. There are also votives that he collected from Aleppo because he had been a soldier in the Ottoman Army. His collection dates from 1905 until 1947 and it gives us a clear picture of the living society during that period. Canaan was very active as a doctor and established the first special clinic in Jerusalem in his house, but he is better known as an ethnographer and anthropologist. Any scholar wanting to study Palestinian heritage has to study Canaan’s articles. He used examples from his collection in his writings.

OP: What is the evil eye?

BJ: Mostly you can describe it as jealousy, people being jealous of each other. The technique of the amulets, as Canaan wrote, is to use shiny pearls so that the eyes concentrate on that amulet. They use many colours – blue, yellow, white, orange – to attract people, to concentrate their gaze on the beads. It deflects the evil eye or other diseases.

OP: So, looking is dangerous?

BJ: The act of looking, yes. There is also something about the sound of the amulet. They believe that the evil eye, the devils and demons, run away from the sound… This is a very interesting amulet because these are beads against different diseases. This is against frustration. There are some diseases that Canaan thought were not just medical – more like madness – which needed social help rather than medical help. For example, people sometimes believed that they had a genie in them when they were in good health. Or they thought that their son was sick because somebody glimpsed him, but their son was not actually physically sick. It was very important for Canaan to know about their beliefs so that he could help them. Some people used to wear black pearls, which are also against frustration… depression. He couldn’t give them medicine for that, but he could advise them how to deal with it.

He wrote a catalogue describing each piece – the amulet – and sometimes he wrote the date he collected or bought it. It is in German mostly and he translated it into Arabic. It might also be his wife’s handwriting because he married a German woman – Margot Canaan [née Eilender] – and she helped him a lot with the collection. If you compare with a museum, where there is a form to register each piece, he didn’t do a systematic job. We don’t have a lot of information. Because he was a collector, the most important thing for him was to study the amulets and keep them so that he could show people and understand how they worked.

OP: Has there been a lot of research into the collection?

BH: Actually, there has been no real research into Canaan’s amulet collection. Nobody has done it, even until today.

OP: Can you tell me about the importance of the collection on a national level?

BJ: The collection is very important for us Palestinians and for Middle East scholars because it gives you a clear picture of society in the first half of the 20th century. If you look at his writings and the folk beliefs behind all of these amulets you get a clear picture about how people used to live, particularly in the villages. Canaan was from a movement – Salim Tamari wrote about it – and his circle were aware that something was coming. I don’t mean the occupation but rather a difference in the way people were thinking. They wanted to preserve this for future generations. He was very close with Gustav Dalman, a very important scholar who studied Palestinian society, and Stephan Hanna Stephan who wrote about Palestinian village songs.

OP: So, it’s a response to modernity?

BJ: To the identity and the modernity of the Ottoman period. If you study this collection you can see its diversity. There are Jewish, Christian and Muslim amulets. Actually, it’s mixed because most of the amulets that Muslim sheikhs made – and Canaan collected – were for Christian women or Christian families and there are also Jewish amulets that were used by Muslims and Christians, and Christian amulets used by Muslims. When you see this mixture, you understand how people used to live together as neighbours before the political conflict.

Here is another interesting piece. At the beginning we thought these were cookies, but they are actually incense with Christian symbols stamped on them. St George is very famous in Palestinian popular beliefs. Al Khidr is the name that the Muslims give to St George and he is famous because many Muslim women go to pray to Al Khidr.

This is another kind of paper talisman: a pilgrim’s certificate, which was given to people in Jerusalem to certify that they had visited the holy places. A lot of people who went as pilgrims to Mecca went to Jerusalem when they came back, because the Al Aqsa mosque is the third most important mosque in Islam after Mecca and Medina. These were mostly issued by the Ansari family, who used to be the keepers of the Al Aqsa mosque and the Dome of the Rock. It was a tradition that was ended by the occupation. This ran parallel to the certificates that churches used to give to people, saying that they had visited the holy places in Palestine. It became a tradition, but it was also a business because people paid for these certificates.

OP: Can you tell me more about the paper talismans?

This is a very important amulet that people used to have in their houses. You can find some part of this amulet in the containers that I showed you earlier. The story written in the amulet is about King Solomon – Prophet Solomon. One day he was wandering in a field and he saw a very ugly woman, so he caught her and asked her, “What are you doing here?” She told him that she is a demon and that her job is to make trouble for people. He held on to her and said I am not going to leave you until you give me something that will protect people from you, and so she gave him these seven talismans. They protect different kinds of things: health, happiness and also the house.

OP: What happened to the collection in 1948?

Because Canaan was very active politically he knew that the area was on the verge of a war, so in 1948 he took his collection from his house and put it in the YMCA in West Jerusalem. By moving his collection, he saved it, because his house in the Musrara quarter was bombed. His daughter said that her mother and father used to go each day to the city wall of Jerusalem to look at their house burning. He later saw some people going into his apartment and taking some of his books. I have heard that there are more than 30,000 Palestinian books in storage at the Hebrew University. It seems fair to assume some of Canaan’s books are there.

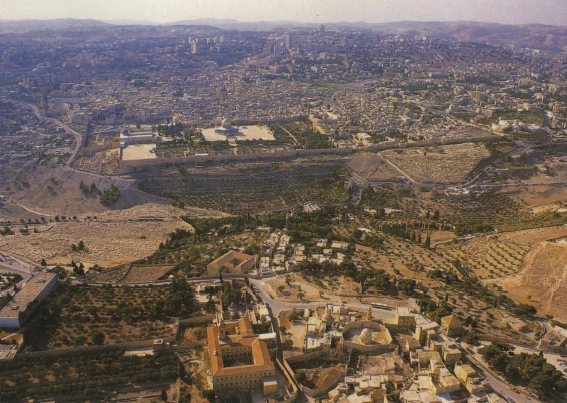

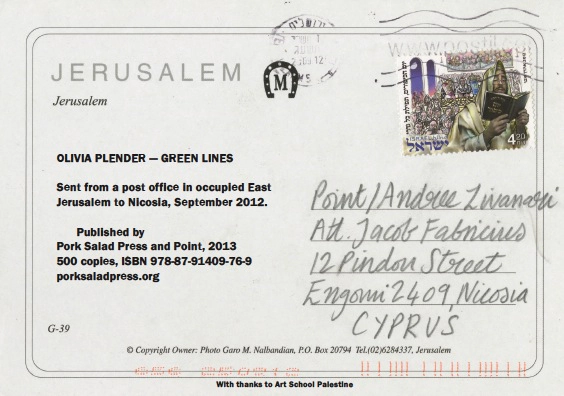

Green Lines, artist’s book, 2013

Green Lines, artist’s book, 2013

Green Lines, 2013

artist’s book, published by Pork Salad Press and Point

A series of postcards sent from a post office in occupied East Jerusalem to Nicosia September 2012

‘On a visit to Bethlehem I was given a tour of the Narrative Museum, in the basement of the Peace Centre on Manger Square. We entered from a back street into a series of dimly lit rooms, recently designed and filled with the latest museum display technology. The Palestinian curator led us through the empty vitrines, while describing the stories and objects that will be presented there in the future. The one historical artefact already in situ was a column of building rubble, which, as far as I remember, he said had been excavated when the site was refurbished. It clearly illustrated several periods of occupation in the history of Palestine; a vertical slice starting with Roman remains at the bottom, followed by the Ottoman period and topped by the British Mandate. After the tour, the curator apologised for being so brief and returned to yet another meeting with the project’s international partners, in order to argue over untold stories from the current occupation that might one day fill the empty vitrines.’

Further Reading

Green Lines, an artist’s book by Olivia Plender, published by Pork Salad Press, 2012

(buy the book)‘Points of Departure’, Delfina Foundation, London, 2013

(view here)