Olivia Plender and Hester Reeve, The Re-inauguration of The Emily Davison Lodge, 2010

series of photographs

The Emily Davison Lodge, 2010–ongoing

a collaboration between Olivia Plender and Hester Reeve

In 2010 Hester Reeve and I were invited by The Women’s Library, London, to make an artwork in relation to their feminist history archive, for the exhibition ‘Out of the Archives’ curated by Anna Colin. Our response was to reopen The Emily Davison Lodge, which takes the name of a celebrated suffragette who died under the king’s horse while trying to interrupt the Epsom Derby. The original lodge was established by her friends shortly after Emily Wilding Davison’s death in 1913, in order to ‘perpetuate the memory of a gallant woman by gathering together women of progressive thought and aspiration, with the purpose of working for the progress of women according to the needs of the hour.’

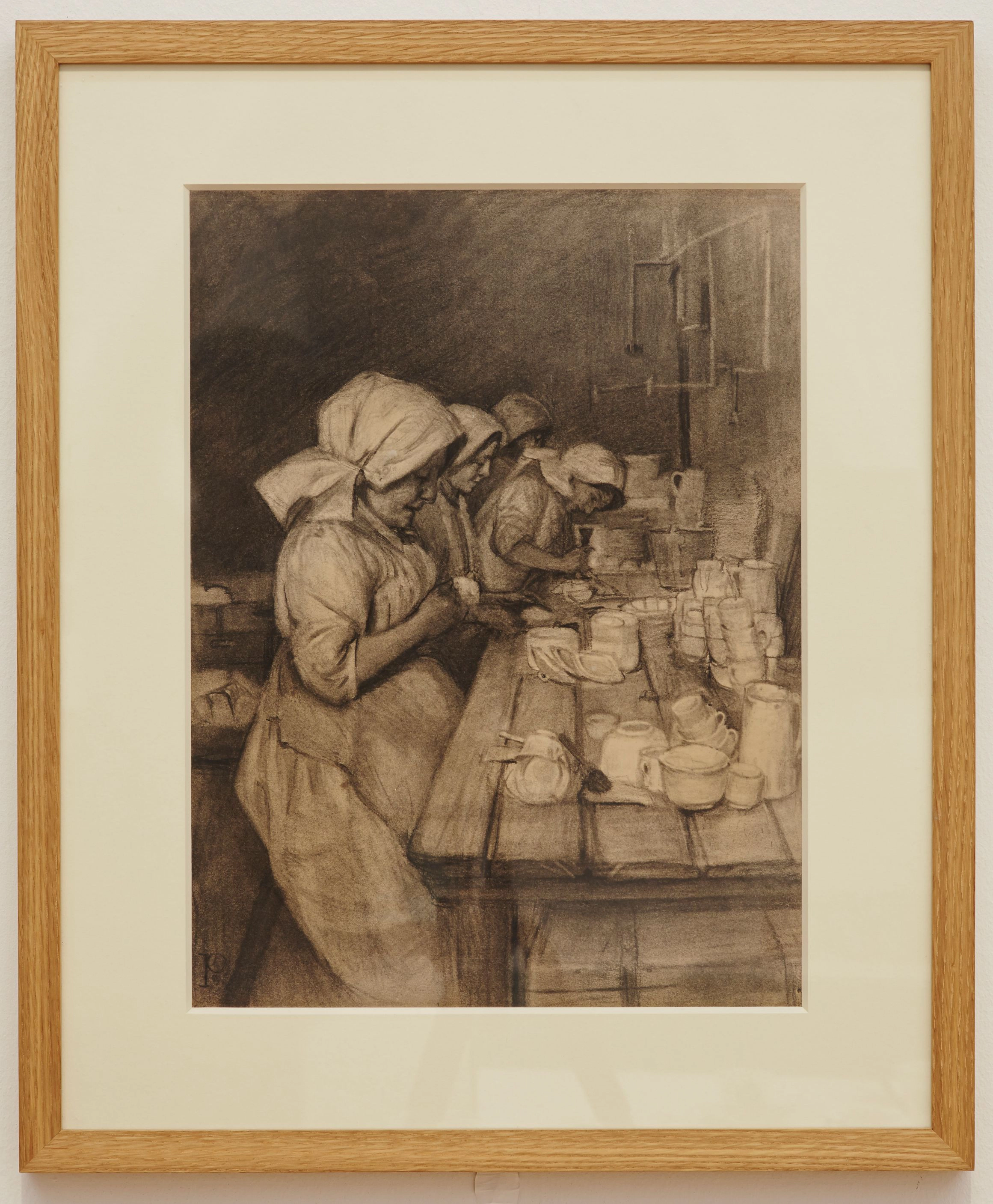

Sylvia Pankhurst, On a Pot Bank: Scouring and Stamping the Maker’s Name on the Biscuit China, 1907 charcoal on paper

Having re-inaugurated The Emily Davison Lodge, our first action was to write an Open Letter to Tate Britain (2010). In the archives of The Women’s Library, we came across a drawing by activist Sylvia Pankhurst, a charcoal depiction of women working in a ceramic factory. Our letter demanded that the Tate address Sylvia Pankhurst’s absence from the collection. Pankhurst studied at the Manchester School of Art and the Royal College of Art in London, and produced a diverse body of art works, including an extensive series of drawings and paintings from 1907 documenting women’s working conditions in Britain. In fact, many of the women who participated in the campaign for women’s suffrage had been trained at art schools, although very few of them are represented in major museum collections.

To: Head of Collections

Tate Britain

Millbank

London SW1P 4RG

May 13th 2010

Dear Ann Gallagher,

We are writing to you to request an appointment to discuss the establishment of a gallery room at Tate Britain, devoted to the work of the British artist Sylvia Pankhurst.

Sylvia Pankhurst’s name is well-documented within social and political history, on account of her celebrated mother and family’s campaign for female suffrage via the establishment of the Women’s Social & Political Union (WSPU) in 1903. But less celebrated is how, aside from being a leading figure of the campaign to win women the vote in this country, Sylvia Pankhurst was also a highly skilled, versatile and pioneering artist in her own right. Through our recent research into her work, we are saddened by the lack of recognition accorded her as an artist and the ongoing pervasive attitudes within society and the arts that such an omission might stand for. Tate Britain currently has no works by Sylvia Pankhurst in the collection and seems to have omitted specific recognition of any feminist impact upon art history, in its thematic arrangements of British art 1700-present date, despite counterculture and rebel voices having always played a serious role in the formation of British culture.

Sylvia Pankhurst’s practice ranged from drawing to painting, from fine art to craft, suffragette propaganda, banner and movement identity design to public speaking, writing and political activism. In our time, when any singular narrative of the traditional argument of art versus life has expanded beyond any neat categorisation of either, the practice of Sylvia Pankhurst forms the basis for renewed discussion on art’s relationship to ‘change’ – do we in the art world know how to value ‘deeds not words’ in 2010? The suffragette insistence on Deeds Not Words, carried through seventy years later to the women’s lib claim that the personal is political, seems ready for a third stage of reappraisal, in the ongoing fight to realise equality for women, and the representation of female artists within the canon of art history.

Some further historical facts to back up our proposal to accord Sylvia Pankhurst her due place in British art history:

She studied at Manchester Municipal School of Art and then went on to win a scholarship at the Royal College of Art (she was later to challenge them on their prejudice against women artists). Her practice expanded upon becoming a WSPU leader; she designed banners and logos (most notably the ‘angel of freedom’, which featured on badges, tea pots and the front page of Votes For Women, the suffragette newspaper). It is claimed that this is the first instance of a campaigning organisation deliberately using design and colour to present an ‘identity’. Of particular note are her Holloway Broach (1909), a silver design incorporating the portcullis and arrowhead of freedom that was awarded to WSPU suffragettes who had been imprisoned for their actions, and the huge 20-feet banners she designed for the famous fundraising Suffragette Exhibition at the Princes Skating Rink in 1909.

An active militant, Sylvia Pankhurst was involved in some of the key moments of the WSPU campaign. Before the avant-gardes had ripped up their first canvas, she was one of the first to attack an artwork, recognising its status as a symbol of patriarchal power and ‘the secret idol of capitalism’. Other artists of the time acknowledged the power of these actions: for example, Wyndham Lewis gave the movement his blessing in the publication Blast, with the words ‘We admire your energy. You and artists are the only things... left in England with a little life left in them.’

Sylvia Pankhurst was imprisoned many times for her actions. While in Holloway Prison she went on hunger strike alongside other suffragettes, suffered force-feeding and yet also made sketches of prison life so she could publicise the adverse conditions to the outside world. The Penal Reform Union was in fact formed at one of the breakfast-welcomes held upon her release from jail. She also produced one of the first historical overviews of the campaign, The Suffragette: The History of the Women’s Militant Suffragette Movement 1905-10, published in 1911 and later, in 1931, one of the most notable accounts in existence, The Suffragette Movement.

Aside from the art and activism, Sylvia Pankhurst’s particular contribution to the historical force of the suffragette movement was to encourage working women and the poor to take power – depicting a mill woman and a washer woman, for example, on the suffragette members’ card that she designed in 1905. Indeed, her own criticism of the WSPU was that it was too bourgeois, and in 1913 she officially broke ties and founded the East London Federation of the Suffragettes (ELFS), which later became the Workers’ Socialist Federation. Here she worked with people from all strata of society and allowed men to join in the cause:

'I was looking to the future; I wanted to rouse these women of the submerged mass to be, not merely an argument of more fortunate people, but to be fighters on their own account, despising mere platitudes and catch-cries, revolting against the hideous conditions about them, demanding for themselves and their families a full share in the benefits of civilisation and progress.' (The Suffragette Movement, pp. 416-17)

Sylvia Pankhurst always displayed a heightened awareness about the complexities of practising as an artist and yet simultaneously wishing to be of service to society. She wanted to put her art at the service of the poor and yet to fund herself as an artist meant dependence on bourgeois patrons. She questioned, ‘whether it was worthwhile to fight one’s individual struggle... to make one’s way as an artist, to bring out of oneself the best possible, and to induce the world to accept one’s creations, and give one in return one’s daily bread, when all the time the real struggles to better the world for humanity demand another service.’

These conflicts provide a radical backdrop to her ‘representational’ works created when she toured the country making drawings of working-class women in their various places of labour. Some commentators have claimed that a crucial turning point in the Liberal PM Lord Asquith’s antipathy for the women’s vote was when he realised, through Sylvia Pankhurst work and campaigning, just how many British women constituted the nation’s workforce. For all the passion dedicated to political and social reform, Sylvia Pankhurst never faltered to declare that art was her ‘chosen mission... which gave me satisfaction and pleasure found in nothing else.’ (The Suffragette Movement, p. 428)

Pankhurst continued throughout her life to engage with art and politics. She was later close to the leaders of the Pan-African movement and campaigned for the independence of Ethiopia, against Mussolini. She subsequently settled there and is still recognised today by the Ethiopian art world as a serious cultural figure.

We bring these biographical facts to your attention, not just to impress upon you Sylvia Pankhurst’s importance, but to again link such a significant life’s work to the advent of British modern art. She stands as a radical forerunner to the later aims of the European avant-garde; indeed this fact can be backed up by the Italian Futurist Marinetti’s claim that ‘In this campaign for liberation, our best allies are the Suffragettes’ (from Le Futurisme, 1911).

For all of the above, we have nonetheless found no instances of Sylvia Pankhurst being included in books on the relation between art and politics and rarely does one find texts mentioning her art practice on art book shelves, The Women’s Library in London excepting. Ultimately, the great radical nature of her achievement lies in the combination of art and activism. Like her fellow militant suffragettes, Sylvia Pankhurst did not just fight for the vote; she fought for the creation of new forms of political life. Having said ‘I would like to be remembered as a citizen of the world’, she fought for freedom not only for women in Britain, but also for women around the globe. Ironically, she remains an uncelebrated figure within British art, despite contemporary expanded definitions of art and interest in its social agency.

We look forward to a discussion of our request that Tate Britain purchase works by Sylvia Pankhurst.

Yours sincerely,

Olivia Plender & Hester Reeve

The Emily Davison Lodge

c/o The Women’s Library

London Metropolitan University

25 Old Castle Street

London E1 7NT

Olivia Plender and Hester Reeve, The Re-inauguration of The Emily Davison Lodge, 2010

series of photographs

In a simple performative act, the artists become a long defunct organisation… As in many contemporary artworks that delve into the archives, The Emily Davison Lodge has an air of ambiguity, fictionality. Did this organisation actually exist? Or is it a convenient device for the artists to re-ignite a relationship to a history of protest and sisterhood?… Visiting the Women’s Library archive in London, a search for ‘The Emily Davison Lodge’ raised no distinct entries… A listing in Emily Crawford’s The Women’s Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide, gave the following information: EMILY WILDING DAVISON CLUB, 144 High Holborn, London WC, was founded as the Emily Wilding Davison Lodge by Mary Leigh in memory of her friend… The Club was still in existence in 1940 when members of the WFL were informed that they might ‘find it convenient to know that they can get a good mid-day meal at the Emily Davison Club, 144 High Holborn’. From such meagre information a world can be imagined. Somewhere between an organisation and a place, The Emily Davison Lodge is a memorial to friendship and a place to continue political agitation or eat a meal.

—Catherine Grant, ‘Learning and Playing: Re-enacting Feminist Histories’, in Feminism and Art History Now: Radical Critiques of Theory and Practice, edited by Victoria Horne and Lara Perry (London: IB Tauris, 2017)

Olivia Plender and Hester Reeve, The Re-inauguration of The Emily Davison Lodge, 2010

series of photographs

In the exhibition ‘Out of the Archives’ at The Women’s Library, visitors encountered Pankhurst’s drawing On a Pot Bank (1907), alongside our Open Letter to Tate Britain (2010), archival photographs of suffragette artists in their studios, a chap book documenting suffragette attacks on artworks and a series of photographs of The Re-inauguration of The Emily Davison Lodge (2010).

We sent the Open Letter to Tate Britain (2010) and subsequently curated a display of Pankhurst’s artworks there in 2013.

‘Sylvia Pankhurst’, installation view, Tate Britain, 2013

Minutes of the Second Meeting of The Emily Davison Lodge

Held at Tate Britain, London, 10 March 2014

In attendance:

Sally Alexander (Historian), Joan Ashworth (Artist and Researcher, Royal College of Art), Emma Chambers (Curator, Tate Britain), Deborah Cherry (Art Historian), Irene Cockroft (Independent Curator and Writer), Katherine Connelly (Historian), Penelope Curtis (Director, Tate Britain), Michael Harding (Artist), Lara Perry (Art Historian), Olivia Plender (Artist), Hester Reeve (Artist), Irene Revell (Director, Electra), Louise Shelley (Collaborative Projects Curator, The Showroom), Patrick Staff (Artist), Marina Vishmidt (Critic), Melanie Unwin (Curator, Art in Parliament)

Introduction by Olivia Plender (on behalf of the executive committee of The Emily Davison Lodge)

We would like to welcome you all and thank you for coming to this, the second meeting of The Emily Davison Lodge, the purpose of which is to debate the value of holding an exhibition of Sylvia Pankhurst’s artworks at Tate Britain, London.

This is the first solo exhibition of Sylvia Pankhurst’s artworks to be held in a public art institution in the UK and as such represents an historic moment. As many of you already know, Sylvia Pankhurst is well-recognised in the British context for her role in winning votes for women. Along with her mother and sisters, she was part of founding the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) in 1903, which was the militant wing of the early twentieth-century campaign for women’s suffrage in Britain. However, less well-known is that she also fought against racism and imperialism. When Mussolini invaded Ethiopia in 1935, she was one of the few figures on the European left who associated this African struggle with the fight against fascism in Europe. In fact, she died in Ethiopia, having moved there towards the end of her life at the invitation of Haile Selassie. She also established the East London Federation of the Suffragettes (ELFS) in the poorest part of London and was later expelled from the WSPU by her mother Emmeline and sister Christabel, because of her socialism. Subsequently, the ELFS became the Workers Socialist Federation in 1918, the first communist party in England, and was briefly affiliated with the Third International.

Sylvia Pankhurst was also an artist, having trained at the Manchester School of Art and then the Royal College of Art in London. This exhibition of her artworks at Tate Britain is curated by The Emily Davison Lodge, in collaboration with Tate curator Emma Chambers. It came about as the result of an Open Letter to Tate Britain, in which we demanded that the museum acknowledge Sylvia Pankhurst and the other neglected female artists who were a part of the suffragette movement. In early twentieth-century Britain, art schools, particularly the Slade in London, were among the few higher education institutions where women could gain access with relative ease. It is because of this fact that art had a large role to play in the WSPU as a movement, through associations such as the Suffrage Atelier and the Artists’ League. The WSPU also initiated a sustained campaign of attacks on artworks in museums around the UK as part of their militant actions directed against ‘the fetish of private property’. Most recognised is Mary Richardson’s attack on the Velazquez painting of Venus in the National Gallery with a small axe in 1914, which has entered into art history. Less well-known is that this was one of dozens of artworks that the British suffragettes targeted.

The Open Letter to Tate Britain was a set of demands as well as an artwork. It was initially part of a series of works commissioned for an exhibition called ‘Out of the Archives’, curated by Anna Colin at the Women’s Library, London, in 2010. Four years after we posted the letter, a display of Sylvia Pankhurst’s artworks opened at Tate Britain.

Address by Hester Reeve (on behalf of the Executive Committee of The Emily Davison Lodge)

The Emily Davison Lodge was re-inaugurated in 2010, at The Women’s Library, London. It takes the name of one of the most famous British suffragettes, who died under the king’s horse while trying to interrupt a race called the Epsom Derby. The original Lodge was established in her memory shortly after her death by two militant suffragette friends, Marie Leigh and Edith New. Its aim was ‘To perpetuate the memory of a gallant woman by gathering together women of progressive thought and aspiration, with the purpose of working for the progress of women according to the needs of the hour.’ The Lodge was as much an abstract concept as it was a framework for women to meet and discuss issues together over affordable food. Little is known about its activities, although there is documentation that Sylvia Pankhurst spoke under its auspices in Morpeth, in the north of England, in 1915. When Penelope Curtis, Director of Tate Britain, responded to our open letter, we agreed to curate this exhibition with the institution as The Emily Davison Lodge. We knew that having that name on the gallery wall as an active organisation would signal that the fight for female equality is something that is still being waged.

Sylvia Pankhurst is of course renowned as a political campaigner, which is only right, but little is known about her artwork and no attention is paid to the role of art in her identity. She trained and won awards at both the Manchester School of Art and the Royal College of Art. The story that is typically told is that she ‘gave up art’ at the age of 27, in order to help the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) achieve its political goals. From the contemporary vantage point, where socially engaged and activist forms of art are de rigueur, we would put it that she did not give up art but rather re-focused her creative energies. We decry the fact that her contribution within the field of art and politics has not been recognised by art history and hope that this exhibition is the beginning of according her such status.

The paintings and drawings from the The Women Workers series were never intended for exhibition. She made them to illustrate an article she wrote about women’s working conditions, which was published in The London Magazine in November 1908 – a copy of which is included in the exhibition. This strategy, this foresight, is so typical of Pankhurst and, at the same time, you can quite feel the joy she had in making the actual works, in having a legitimate reason to use paint and work in terms of colour. They have far more aesthetic investment than mere illustrations warrant.

Our aim is to insert not just the work of Sylvia Pankhurst into art history, but also that of other creative militant suffragettes. We want to know their names, we want the impact of what they did and the multi-levelled ways in which they operated – through friendships and behind the scenes acts of protest as prevalent as the public spectacular processions and rushes on parliament – recognised. From today’s perspective these types of actions are instances of extreme creativity. There is much to learn from this that, as yet, has not been learnt. This is a feminist revision as well as an artistic one.

The original Emily Davison Lodge ceased operating at some point in the early 1940s, and while its current reincarnation shares the founding manifesto, we would like to add that The Emily Davison Lodge is a proposition. It suggests a conceptual dwelling place for trying out new, radical and creative types of campaigning, while providing a framework for us as artists to progress in our work of researching the suffragette as a militant artist. We accept that this challenges our artworks to take on agency, to affect change in the world where possible, which is modestly reflected in the Open Letter to Tate Britain we wrote and which resulted in the realisation of this Sylvia Pankhurst display.

Lastly, but most importantly, The Emily Davison Lodge stands as a proposal. We hope the name of a famous militant suffragette and the motto ‘To meet the needs of the hour’, will encourage people and projects interested in feminist strategies and the relationship between art and social change to come forward, and either work with us or use the Lodge as an umbrella to help them forward their cause.

The Artworks Explained by Lara Perry

The introduction was followed by a tour of the artworks by art historian Lara Perry, in which the assembled party learnt the following:

In The Women Workers series, Sylvia Pankhurst uses her skills as a painter in order to show the viewer the unromantic reality of women’s working conditions, the bare feet of the textile workers and red hands of the herring cutter, the repetitive nature of piece work, child labour and the subordination of women workers to male workers, for whom she also has sympathy. In the article that she wrote for The London Magazine in 1908 to accompany the paintings, she calls the little girl who appears in the painting of a ceramic factory in 1907 ‘the slave of a slave’ as she is restricted to the lower paid, unskilled work of preparing the clay for the male ‘thrower’ to turn on the pottery wheel. Some of the portraits focus on a single worker, such as the woman minding a pair of fine frames in a Glasgow cotton mill, and aim to show the humanity of the individual, but there are also, unusually, images of women working in groups. Through these artworks, Pankhurst made a powerful argument for improvements in working conditions and pay equality with men.

The working conditions in each factory varied. In a Leicester boot factory, the women are shown hunched over the pieces as they sew them together. Despite the fact that this was a small producers’ co-operative factory, Pankhurst was saddened by how alienated the workers were from the final product of their labour. In the ceramic factories of Staffordshire, where many of the paintings were made, the lead glaze used was extremely damaging to the health of the workers. Pankhurst was disgusted when she found out that reasons for its use were purely commercial. In contrast, in a painting made in the Wedgewood factory, which had better conditions than most, she foregrounds the beautifully decorated soup tureen in the image, in order to emphasise the craft that has gone into it and the artistic nature of the work.

Pankhurst also made drawings while in prison for suffragette activities, which were intended for publication alongside an article publicising the appalling prison conditions. Many suffragettes served sentences, going on hunger strike in protest against the government’s refusal to categorise them as political prisoners and enduring the torture of force-feeding. The Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) were skilled at symbolic gestures, and through ritual were able to normalise the extraordinary and far from respectable behaviour that participation in the movement called for. Suffragette prisoners were usually met at the prison gates upon their release, and often paraded through the streets to a celebratory meal or tea where they were presented with a medal or certificate. The exhibition includes the Holloway Brooch (c. 1909) in enamel silver, which is one of these medals: it shows a design by Sylvia Pankhurst based on the gates of Holloway women’s prison, where many of the suffragettes served their sentences. On show is an illuminated address given to a suffragette named Elsa Gye, to commemorate her having served a prison term for the cause. This was designed by Pankhurst and includes the WSPU’s logo, called the ‘angel of freedom’. The influence of the Arts and Crafts movement on Pankhurst is clear in the medievalism of the logo, which appeared on banners, membership cards and a tea set sold to raise funds for the WSPU.

Sylvia Pankhurst saw art and beauty as essential to dignity and the opposite of alienated labour throughout her life. The central premise of the exhibition, as outlined by Olivia Plender and Hester Reeve in the discussion, was that once she had become a full-time political campaigner, her actions continued to reflect these values; she established a co-operative toy factory in London’s East End with toys designed by artists, turned to writing plays, fiction and history and towards the end of her life was even involved in the art scene in Ethiopia. The Emily Davison Lodge advocates for Sylvia Pankhurst’s inclusion in art history and aims to move away from the usual story of her career. The idea that Pankhurst gave up art in order to go into politics reiterates the conservative notion of art as a sphere separate from politics. The representatives of The Emily Davison Lodge present at the meeting argued that she did not so much abandon art for political action, as substitute one form of artistic representation for another.

A Feminist Intervention in the Canon

A discussion ensued around how The Emily Davison Lodge had taken a strategic position in their Open Letter to Tate Britain to focus on Sylvia Pankhurst, as she was one of the best-known figures within the movement and also because it was possible to build a coherent argument around The Women Workers series of paintings. The aim was to intervene in how this history is written, initially targeting Tate Britain as the institution that decides who counts in British art. It was stated by Olivia Plender and Hester Reeve that with the exception of a few feminist art historians, such as Lisa Tickner in her book The Spectacle of Women, none of the artworks to be discussed at the meeting had been addressed by art history – and to the best knowledge of The Emily Davison Lodge at that time they had not previously been exhibited by any art institution.

The question was asked, as to why so few female artists make it into art history? While acknowledging the obvious discrimination taking place, the discussion centred on the more subtle factors at play. One explanation offered for Pankhurst’s absence from the canon was her refusal to specialise. In her introduction to The Sylvia Pankhurst Reader, historian Kathryn Dodd speaks of the ‘radical reconstruction of intellectual ideas and categories that took place from the 1880s to 1920s… [when] the expert academic emerged as the authoritative intellectual figure. In these circumstances, to cling to Utopian beliefs in the wholeness of knowledge and experience, as Pankhurst did, to be a political activist and an artist and a writer – of history, and politics, and poetry – was a good way to be at best ignored, or at worst derided.’

In much of the theory and writing around the recent social turn in art, in particular Nicolas Bourriaud’s Relational Aesthetics, the role of feminism is alarmingly neglected. Second-wave feminist artists in the 1970s, emerging from the Women’s Liberation Movement, were involved in developing many of the methods behind the social practices that are currently celebrated on the global biennial circuit. The group discussed how these artists often worked outside of the mainstream, forming collectives both as a survival strategy and in order to find forms and establish institutions that reflected their own political values, rather than those dictated by a market-driven art world. Their works were often made collaboratively, which were not easily collectable commodities as they challenged the conventions of authorship. These works are rarely found in museum collections because much art history over-emphasises the role of solo artists in historical movements.

But does this matter? The consensus at the meeting was that it does, and many of those present referred to Griselda Pollock’s work in her book Differencing the Canon (1999):

In order to shift the lines of demarcation we must attend both to the level of enunciation – what is said in discourses and done in practices in museums and galleries – and to the level of effect, that is, how what is said articulates hierarchies, norms asserting elite white masculine heterosexual domination and privilege as ‘common sense’ and insisting that anything else is an un-aesthetic aberration: bad art, politics instead of art, partisanship instead of universal values, motivated expression instead of disinterested truth and beauty.

The group agreed that the gesture embodied in The Emily Davison Lodge’s Open Letter to Tate Britain owed a great deal to second-wave feminist artists and art historians such as Pollock. In the 1970s they were already looking back to the first wave of feminism and similarly aimed for visibility of more female artists. Those present at the meeting debated the question of what a gesture like this, borrowed from the 1970s feminist movement, means today. It was felt that while the aim to intervene in the canon was in a sense successful, as there was indeed a show of Pankhurst’s works at Tate Britain, it had come at a price and with much compromise.

Many voices, both female and male, are unheard by the disciplining and educational institution that is the museum, as they do not speak in ways that the institution recognises as legitimate. Subsequently (as The Emily Davison Lodge reported), a year or so into the process of negotiating the Sylvia Pankhurst display, a strange question was suddenly asked by Tate: ‘But is the work actually any good?’ Perhaps this was politics not art, partisan and ‘motivated expression’ rather than ‘disinterested truth and beauty’ after all. The representatives of Tate Britain present at the meeting defended the institution. But they agreed that one of the compromises of the project was that, in order to overcome this hurdle, The Emily Davison Lodge had deliberately shaped the narrative of the artist Sylvia Pankhurst into a form that the museum could comprehend. For example, singling Pankhurst out as a solo artist in their letter and mentioning the responses to the suffragette artists’ activities by well-known male avant-garde artists (such as the futurist Marinetti and the British Vorticists) as a means of legitimising them.

The Emily Davison Lodge stated that they had accepted the ideological apparatus of the Tate – which includes corporate sponsorship and also the conditions of work at the museum – in the interests of opening up a dialogue about the lack of representation of female artists, in both the historical and contemporary collection and exhibitions, and making their voices heard. At this point, artist Patrick Staff interjected and suggested that the project was a kind of Trojan horse. But others felt that Tate Britain, to an extent, was able to absorb Pankhurst’s artwork, and its politics, into an avant-garde logic of novelty and newness. The institution of art was hardly challenged.

The Emily Davison Lodge reported that they had also had problems when it came to their own working conditions, as Tate Britain not only seemed reluctant to commit funds to the project, only sourcing works in the London area, but were also reluctant to pay them anything other than a token fee for their work. It was noted that this practice is unfortunately very common in the art world, especially when it comes to larger and more powerful institutions. Olivia Plender and Hester Reeve pushed Tate Britain to fundraise for the project so that they were able to spend time on it, away from other paid work, but to no avail. They expressed concern that this had limited the scope of the project. A key aim had been to locate and record as many of the works of The Women Workers series as possible, another had been that Tate Britain invest in purchasing Pankhurst’s artwork, securing it for future generations.

Addition to minutes post-meeting:

During this process, one of the founder members of the re-inaugurated Emily Davison Lodge had a dream in which she was at an exhibition opening with Penelope Curtis, the director of Tate Britain (who was also present at the meeting). In the dream they were standing in front of a plinth supporting a small sculpture, a dummy cast in bronze (or pacifier in American English). Curtis told her that this was a participatory artwork and tried to persuade her to put the bronze dummy in her mouth. In British English the word dummy implies being made dumb, or speechless, whereas in American the name implies passivity – to be made passive. Either way, Olivia Plender (whose dream it was) was clearly feeling both infantilised and as if there was an attempt on the part of the institution to silence her. In keeping with this atmosphere, she did not confront Penelope Curtis with her dream at the meeting.

Perhaps this was a failed attempt at engaging the museum in institutional reform? However, as was discussed, the reality of showing at such a large museum such as the Tate is very complex and, with thousands of people viewing the artworks, there were many unanticipated effects from the exhibition, which would not have been possible had the works been shown in a more alternative venue.

At this point, feminist historian Sally Alexander (who was an organiser of the first national UK Women’s Liberation movement conference held at Ruskin College, Oxford, in 1970) passionately raised the question: ‘How does this history address you? How can we let this history address us?’ There was a debate about the relevance of Pankhurst’s work to contemporary feminist struggles. The Emily Davison Lodge insisted that their interest in Pankhurst was in no way nostalgic. They argued that this history is important to address today as hard-won equal rights are currently under threat. Women are disproportionately affected by the contemporary climate of ‘austerity’ and welfare cuts, with many being pushed back into low-paid and unwaged labour.

Olivia Plender and Hester Reeve mentioned that they have been contacted by many different feminist organisations who find Pankhurst’s artworks relevant to their struggle: for example, the National Association of Women, an organisation with close ties to the trade union movement. At the NAW’s annual Sylvia Pankhurst memorial lecture, The Lodge addressed an audience whose members made comparisons with many different political causes, including the miners’ struggle of which many present were veterans. The Emily Davison Lodge was subsequently invited by Reclaim the Agenda, a coalition of feminist organisations based in Belfast in Northern Ireland, to bring Pankhurst’s work there for International Women’s Day.

It was at this point in the meeting that Sally Alexander and feminist art historian Deborah Cherry pointed out that Pankhurst’s artwork had actually been shown once before in a major public art institution. This was in the 1980s in an exhibition about the Edwardian era curated by Cherry at the Barbican Art Centre in London. None of the others present had heard of the show, despite being researchers into Pankhurst’s work. In an interesting turn of events, it turned out that Cherry had at that time attempted dialogue with Tate but without success. Tate was then totally uninterested. Therefore, both women deduced that the current recognition by the institution of Pankhurst’s work and the fact that Tate Britain has a female director is a sign of progress. They argued against the notion that the artworks had ever disappeared from view though, because for them they had never gone away. These voices may have been unheard within certain contexts, but they are loud and clear in others.

Actions

Following the disclosure that the works had already been shown in a major public art institution, those assembled at the meeting felt that a temporary display at Tate Britain is not enough to secure the original aim of winning a place for Sylvia Pankhurst in art history. It is considered necessary to make a publication about her artworks that can become a permanent feature in libraries, otherwise the work is in danger of once again disappearing from view.

There are plans to expand the membership and hold a weekend working party-conference during which a banner is designed and created for The Emily Davison Lodge.

Minutes signed off by Hester Reeve and Olivia Plender, 20 March 2014.

Postscript

In December 2018, the Tate announced that they were purchasing four paintings by Sylvia Pankhurst to add to their collection, a purchase surrounded by publicity because 2018 marked the centenary of the first women to gain the right to vote in the UK. In a letter to The Guardian, which they declined to publish, Hester Reeve and I wrote the following:

Dear Madam/ Sir

Your article of 20 December 2018, titled: ‘Sylvia Pankhurst paintings of women at work acquired by Tate’, omits to mention the display of Sylvia Pankhurst’s artworks shown at Tate Britain in 2013-14, which was curated by The Emily Davison Lodge (Olivia Plender and Hester Reeve), with Tate curator Emma Chambers. The four paintings by Pankhurst recently purchased by Tate Britain, were originally shown in this exhibition. Further, there is no mention that it was The Emily Davison Lodge that initially introduced Tate Britain to Pankhurst’s artistic practice in the form of an artwork titled Open Letter to Tate Britain, in which we demanded that the museum add her to their collection. This letter was exhibited at The Women’s Library, London, in 2010, and again at Tate Britain, in conjunction with the Sylvia Pankhurst display. It was intended as a feminist intervention in the canon of art history, to correct the unjust omission of Pankhurst and other female artists like her. Although we are extremely pleased that our project has had such a successful outcome, it seems ironic that the eight years of hard work undertaken by The Emily Davison Lodge to raise her profile as an artist and make this possible, has now been erased from the story.

Yours Sincerely

Olivia Plender and Hester Reeve

We could also have added a second irony, which was that the real focus of The Guardian article was the (female) betting billionaire who had funded the purchase. Contrary to our original intentions, the inclusion of Pankhurst’s works in the Tate collection had become a vehicle for publicity for the institution’s corporate sponsors, allowing them to attach themselves in the public imagination to a progressive cause.

Further Reading

‘Learning and Playing’, Catherine Grant, published in Feminism and Art History Now: Radical Critiques of Theory and Practice, edited by Victoria Horne and Lara Perry (London: IB Tauris, 2017)

(download)Feminism and Art History Now: Radical Critiques of Theory and Practice, edited by Victoria Horne and Lara Perry (London: IB Tauris, 2017)

(view here)Feminist Afterlives: Assemblage Memory in Activist Times, Red Chidgey, including a chapter on The Emily Davison Lodge and cover art by Olivia Plender (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018).

(view here)The Guardian, ‘Sylvia Pankhurst paintings of women at work acquired by Tate’, 20 December 2018

(view here)